TAU Study Reveals Advanced Visual Processing Evolved Hundreds of Millions of Years Ago

Research

TAU Study Reveals Advanced Visual Processing Evolved Hundreds of Millions of Years Ago

A new study from the School of Neurobiology, Biochemistry, and Biophysics reveals a surprising insight into the operation of the ancestral brain: the visual cortex of turtles is capable of detecting unexpected visual stimuli in a way that is independent of their position on the retina, a property that, until now, was thought to exist only in the highly developed cortices of mammals, including humans. In light of these findings, the research team assesses that advanced brain mechanisms previously thought to be unique to mammals were already present hundreds of millions of years ago.

The study was led by Milan Becker, Nimrod Leberstein, and Dr. Mark Shein-Idelson, researchers in the Department of Neurobiology and the Sagol School of Neuroscience at Tel Aviv University. The study was published in the prestigious journal Science Advances.

The researchers explain that reptiles and mammals diverged from a common ancestor approximately 320 million years ago. Since that time, the mammalian brain and the cerebral cortex in particular — has undergone dramatic development, becoming complex, large, and folded. The reptile brain, by contrast, is regarded as simpler and more like the common ancestor of reptiles and mammals. Therefore, when a sophisticated computational mechanism in mammals is discovered also in the brain of a turtle, it suggests that this mechanism already existed in the brains of the ancestral amniotes – the first animals that completed the move onto land.

Research team (Left to right): Milan Becker, Nimrod Leberstein & Dr. Mark Shein-Idelson.

In the study, the researchers focused on the turtle’s dorsal cortex, a region considered an evolutionary homolog of the mammalian cerebral cortex. Using neural recordings in awake animals, along with eye-movement tracking, the researchers examined how the turtle brain responds to repeatedly presented visual stimuli compared with “deviant” stimuli that appear in unexpected locations in the visual field.

Dr. Shein-Idelson: “The truly surprising result emerged when we examined what happens when the turtle moved its head or eyes. Such movements shift the image on the retina and can create ‘confusion’ in the visual system. Yet in turtles, the response to both the deviant and the regular stimulus remained consistent, despite frequent changes in the viewing angle. In simple terms, the turtle’s brain ‘understands’ that something new has occurred in the environment, even if the image is seen from a different angle and no longer falls on the exact same spot on the eye.”

The researchers also found that the turtle’s self-generated movements, such as shifts of the head or eyes, hardly elicit any brain response, even though they substantially alter the image received by the eye. In contrast, a small but unexpected change in the external environment strongly activates the brain. This indicates an ability to distinguish between stimuli resulting from self-motion and new information that requires attention.

According to the researchers, these findings change the way we understand brain evolution. Until now, it was believed that view invariance is hierarchically computed as information travels from low to high visual areas as observed in monkeys and humans. The new study presents a different picture: even in the brain of early terrestrial vertebrates with a simple cortex, like those of the turtle’s ancestors, there already existed an ability to detect important events in the environment invariantly of viewing angle.

The researchers believe that this ability helped animals understand their spatial environment, learn, and survive complex terrestrial environments. Remarkably, even without a large and folded cerebral cortex, turtles possess a smart system capable of recognizing when something truly important is happening around them.

Dr. Shein-Idelson concludes: “This study demonstrates how the brains of turtles offer a unique window into the evolutionary past. Because turtles and mammals diverged from a common ancestor hundreds of millions of years ago, the discovery of advanced brain mechanisms in turtles suggests that these abilities either evolved hundreds of millions of years ago or convergently evolved due to similar environmental pressures in both lineages. The findings suggest that the ability to detect new and important occurrences in the environment, without being influenced by self-generated head and eye movements, is one of the cornerstones upon which the cortex evolved and points to the importance of this essential computation.”

Research

A new TAU study shows that strength training is the most effective way to lose weight while preserving muscle mass for both women and men.

A new study conducted at the Gray Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences and the Sylvan Adams Sports Science Institute at Tel Aviv University reveals a clear conclusion: strength (resistance) training is the most effective tool for achieving “high-quality” weight loss, reducing body fat while preserving, and even increasing, muscle mass.

The study was led by Prof. Yftach Gepner, together with Yair Lahav and Roi Yavetz, and was published in the scientific journal Frontiers in Endocrinology. The researchers analyzed data from hundreds of women and men aged 20–75 who participated in a structured weight-loss program. All participants adhered to a low-calorie diet with a controlled energy deficit, but were divided into three groups based on their chosen activity: no physical exercise, aerobic exercise, or resistance training.

The findings show that while total weight loss was similar across all groups, a significant difference was found in the composition of the weight loss. Participants who performed strength training lost more fat than those in the other groups, and at the same time were the only ones who succeeded in preserving and even increasing their muscle mass. In contrast, participants who did not exercise, as well as those who engaged in aerobic activity alone, lost a substantial portion of their muscle mass as part of the weight-loss process.

The research team explains: “Although total weight loss was similar among all participants, the key difference lay in the composition and quality of that loss. While weight loss without strength training, and even with aerobic activity alone, was accompanied by loss of muscle mass, strength training led to weight loss based primarily on loss of fat, while preserving and even increasing muscle mass. This means that weight loss achieved through strength training is not just a decrease on the scale, but a healthier, more stable, and more effective long-term process.”

The research team (Left to right): Yair Lahav, Roy Yavetz & Prof. Yftach Gepner.

Muscle mass plays a central role in health and metabolism. Muscle constitutes about 40% of body weight and is responsible for a significant portion of daily energy expenditure, even at rest. When muscle mass declines, metabolic rate decreases, weight loss becomes more difficult, and the likelihood of regaining weight after dieting increases. Therefore, weight loss that does not preserve muscle may be less sustainable and potentially harmful in the long term.

Beyond that, maintaining muscle mass is essential for everyday functioning, strength, stability, and balance. Loss of muscle can impair physical ability, increase the risk of injuries and falls, and may even accelerate the development of sarcopenia age-related muscle degeneration that can also affect relatively young individuals during unbalanced dieting.

The study also demonstrated a clear advantage of strength training in reducing waist circumference a key indicator of abdominal obesity and cardiometabolic risk. The greatest reductions in waist circumference were observed among the participants who engaged in strength training and were found to be strongly associated with fat loss, highlighting this type of exercise’s contribution to heart and metabolic health.

According to the researchers, the findings underscore that not all weight loss is equal in quality. “Good” weight loss reduces body fat, preserves muscle, and supports health and long-term weight maintenance. The study’s conclusion is clear: incorporating strength training into weight-loss programs is not a luxury, but an essential component of healthy, effective, and sustainable weight loss for both women and men.

Prof. Gepner concludes: “Our study shows that weight loss should not be measured only by how many kilograms we lose, but by the quality of that loss. When appropriate nutrition is combined with strength training, it is possible to reduce fat effectively while preserving and even improving muscle mass, a critical factor for metabolic health, daily functioning, and long-term weight maintenance. Our findings make it clear that strength training is not just for athletes, but a vital tool for anyone who wants to lose weight in a healthy, safe, and sustainable way, women and men alike.”

Research

Preliminary TAU findings suggest noninvasive brain stimulation may reduce intrusive PTSD symptoms

A new study conducted at Tel Aviv University introduces an innovative approach to treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generating particular interest in light of the sharp rise in the number of individuals coping with the condition following the events of October 7 and the Iron Swords War. According to the study’s preliminary findings, treatment using noninvasive brain stimulation succeeded in significantly reducing intrusive memories, such as flashbacks and intrusive thoughts, which are considered among the most severe and treatment-resistant symptoms of PTSD.

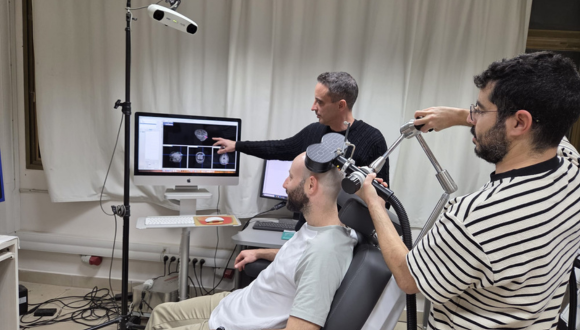

The study was conducted in the laboratories of Prof. Nitzan Censor and Yair Bar-Haim from the School of Psychological Sciences and the Sagol School of Neuroscience at Tel Aviv University. It was led by doctoral students Or Dezachyo and Noga Yair, in collaboration with the laboratory of Prof. Ido Tavor. The research team included Noga Mendelovitch, Dr. Niv Tik, Dr. Haggai Sharon of Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (Ichilov), and Prof. Daniel Pine of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in the United States. The study was published in the scientific journal Brain Stimulation.

Research team (Left to right): Prof. Yair Bar-Haim, Noga Yair, Or Dezachyo and Prof. Nitzan Censor

PTSD affects millions of people worldwide, including soldiers and survivors of terrorist attacks, traffic accidents, and violence. Despite advances in psychological and pharmacological treatments, only about 50% of patients respond well to existing therapies, and intrusive memories continue to burden many of them years after the traumatic event. These memories are not just distressing thoughts; they are vivid, tangible experiences that reactivate the body and emotions as though the trauma were happening all over again.

The researchers focused on the hippocampus — a deep brain structure responsible for the processing, storage, and retrieval of memories. Because direct stimulation of deep brain regions requires invasive intervention, the team employed an indirect and sophisticated method: they identified superficial brain regions that are functionally connected to the hippocampus and stimulated them using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). The precise stimulation site was determined individually for each participant based on fMRI scans, allowing for a personalized treatment approach.

Ten adults with PTSD participated in the initial study, undergoing five weekly treatment sessions. During each session, the traumatic memory was first deliberately reactivated, after which brain stimulation was applied — precisely at the stage when the memory is in a “flexible” state and more open to change, within a process known as reconsolidation. The researchers’ aim was to influence the way the memory is re-stored in the brain, thereby alleviating post-traumatic symptoms.

The results showed a sharp reduction in the severity of post-traumatic symptoms, particularly in the frequency and intensity of intrusive memories, with participants demonstrating consistent improvement. At the same time, brain imaging revealed reduced connectivity between the hippocampus and the stimulation regions — evidence that the effects were not merely subjective but reflected a real change in brain activity.

Illustration of the experimental setup

These findings carry particular importance for IDF soldiers, members of the security forces, civilians exposed to the terror attacks of October 7, survivors of the massacre, and victims of shootings and abductions — Israeli populations in which the prevalence of PTSD is expected to be especially high. Many of them report experiencing intense intrusive memories months after the events. The potential development of a short, noninvasive treatment that directly targets the mechanisms underlying traumatic memories could become a valuable component of the national rehabilitation effort.

According to the researchers, although this was a preliminary study conducted in a small group and did not include a control group, it provides clear proof of feasibility. Larger, controlled clinical trial is already underway at Tel Aviv University, and is required to assess the method’s effectiveness and long-term impact. If the findings are confirmed, this may represent a fundamental shift in the way traumatic memories are treated — addressing not only its emotional consequences, but the underlying neural root itself.

Prof. Nitzan Censor concludes: “These preliminary findings point to a conceptual shift in how we can approach the treatment of PTSD. We are attempting to intervene, in a targeted manner, in the brain mechanism of memory itself — at the moment when it ‘reopens’ and becomes amenable to change. The fact that we observed a consistent reduction in intrusive memories, alongside a measurable change in brain activity, is encouraging. It is important to emphasize that these are still very early results. Nevertheless, especially in light of the current reality in Israel, we hope that continued, comprehensive clinical research will eventually make it possible to develop a noninvasive and accessible treatment that will help many soldiers and civilians return to functional lives, free from the constant intrusion of traumatic memories.”

Research

Researchers warn that patterns seen in the Canary Islands may emerge in other regions worldwide.

A global study by an international research team, including Prof. Omri Bronstein of the School of Zoology, Wise Faculty of Life Sciences and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University - who is leading global efforts to study the wave of sea urchins mass mortalities around the world, presents new and particularly alarming findings: for the first time, evidence of apparent local sea urchin extinction has been found in the Canary Islands.

The study revealed that the genus Diadema (the long-spined black sea urchins many of us are familiar with) is no longer able to produce offspring at this site — a finding that likely indicates local extinction.

The study was carried out by an international consortium including Tel Aviv University scientists in collaboration with researchers from Spain and the Canary Islands. The findings were published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Prof. Bronstein describes the sequence of events over recent decades: “In 1983–84, a mass mortality event of Diadema sea urchins was recorded in the Caribbean islands in the western Atlantic Ocean. This die-off triggered a dramatic ecological shift in the region: with the sea urchins — the habitat’s primary algae grazers — gone, vast algal fields spread, blocking sunlight and causing severe, irreversible damage to coral reefs in the region. In 2022, another mortality event struck the Caribbean, and for the first time the pathogen responsible for the lethal disease was identified. This epidemic spread to the Red Sea by 2023, and by 2024 it was also detected in the Western Indian Ocean, off the coast of Reunion.”

In the current study, a formerly undetected mass mortality event was identified in the Canary Islands, off the coast of Morocco in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, which in fact occurred as early as mid-2022. According to the researchers, this event represents the “missing link” in the disease’s geographic spread. The study also revealed a particularly troubling finding, which likely points to the potential local extinction of the species in the Canary Islands. The study was based on extensive observational data collected through local citizen science, alongside scientific surveys, satellite data analysis (remote sensing), and the collection of samples from the seafloor by the research team.

Prof. Bronstein explains: “Sea urchins reproduce by releasing sperm and eggs into the seawater, where fertilization produces millions of embryos that drift as plankton in the water column. After several days to weeks (depending on the species), the larvae settle on the seabed and develop into juvenile urchins — a process known as ‘recruitment.’ In this study, we discovered that for the first time in history, there are no new juvenile urchins being recruited across several Canary Islands, indicating that the recruitment process has halted since the extensive mortality event that took place there. In other words, the die-off of the adult urchins has been so widespread that the species is no longer able to produce a next generation, if no recruitment occurs, the species may disappear from the region’s ecosystem.”

The researchers note that sea urchin populations are typically characterized by fluctuations — they often decline and later recover. This time, however, the situation is far more severe and appears to be an extinction event rather than a transitional phase. The researchers warn that the pattern observed in the Canary Islands may also unfold in other regions around the world where unprecedented sea urchin mass mortality events have been recorded in recent years — including the Red Sea coast and the coral reef of the Gulf of Eilat.

Prof. Bronstein concludes: “In this study, we identified a mass mortality event of sea urchins that occurred in mid-2022 in the Canary Islands. In its aftermath, it became clear that the affected species is no longer capable of successfully reproducing in this area — a finding that may lead to local extinction, which is expected to have severe ecological consequences. A likely outcome would be the uncontrolled proliferation of algae, which would affect the entire ecosystem — although at this stage, it is difficult to predict exactly in what way.

Prof. Omri Bronstein

Prof. Omri Bronstein is a marine biologist whose research focuses on molecular ecology and the processes that lead to the formation of new species. He is a senior faculty member at the School of Zoology in the George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences and at the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel Aviv University.

Research

New research reveals that activating the brain’s reward system through positive anticipation strengthens the immune response and increases antibody production

Can positive anticipation that activates the brain’s reward system strengthen the body’s immune defenses? A new study by Tel Aviv University, the Technion, and Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov), published in the prestigious journal Nature Medicine, provides the first evidence in humans that brain activity associated with the expectation of reward has a measurable effect on the body’s response to a specific vaccine.

Training the Brain’s Reward SystemThe study was conducted through a collaboration between two research groups: the laboratory of Prof. Talma Hendler, from the School of Psychological Sciences and the Gray Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, together with her former PhD student Dr. Nitzan Lubianiker, at Tel Aviv University and the Sagol Brain Institute at Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov); and the laboratory of Prof. Asya Rolls from The George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, together with her former student Dr. Tamar Koren of the Technion and the Department of Pathology at Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov).

Eighty-five healthy volunteers participated in the experiment. Some underwent special brain training using fMRI neurofeedback technology — a method that enables individuals to learn, in real time, to regulate activity in specific brain regions through reinforcing learning. The aim of the brain training was to increase activity in a key region of the brain’s reward system including the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA), which is responsible for dopamine release in the context of mental activity related to the expectation of positive outcomes and motivation to obtain rewards. Participants were instructed to modulate their brain activity using various mental strategies (e.g. thoughts feelings memories) while monitoring positive feedback about the strategy that was saucerful in regulating their brain.

Immediately after completing the brain training, all participants received a hepatitis B vaccine. The researchers then tracked the immune response through a series of blood tests, measuring levels of specific antibodies produced following the vaccination.

The results showed that participants who succeeded in significantly increasing activity in the brain’s reward region also demonstrated a greater increase in antibody levels after vaccination. The association was specific to the VTA and was not observed in other brain regions used for control purposes (such as the hippocampus), nor in other reward-system areas linked to different reward-related experiences such as pleasure and satisfaction. In other words, the effect was both anatomically and mentally specific.

Dr. Nitzan Lubianiker, photo credit: Sameer Khan/Fotobuddy

Furthermore, an in-depth analysis of the mental strategies participants used during training of the VTA (and not other regions) revealed that those who focused on positive anticipation — feelings of excitement, belief in a good outcome, or the expectation of something positive about to happen (such as a favorite food or a long-awaited meeting) — were able to maintain higher VTA brain activity over time, which was also associated with a better immune response. In other words, the researchers identified a link between reward-system brain activity, a mental state of positive anticipation, and the body’s response to an immune challenge.

According to the research team, this is not “positive thinking” in the popular sense or a New Age slogan, but a measurable neurobiological mechanism — related, among other things, to the well-known placebo effect in medicine (a therapeutic response beyond a specific medical intervention). “We show that mental states have a clear brain signature, and that this signature can influence physiological systems such as the immune system,” explain the researchers.

While the study does not propose a substitute for vaccines or medical treatment, it opens the door to new, noninvasive approaches that may one day strengthen immune responses, improve the effectiveness of medical treatments, and even contribute to fields such as immunotherapy and the treatment of chronic immune pathologies. The researchers note that the study’s findings underscore a broader message: the mind–body connection is not merely a theoretical concept, but a real biological process that can be measured, trained, and potentially harnessed to promote better health.

Prof. Talma Hendler, Photo credit: Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov).

The research team adds that the findings highlight the potential inherent in integrating neuroscience, psychology, and medicine. “Our study shows that the brain is not only a system that responds to the body’s state of health, but also an active player that influences it,” say Prof. Talma Hendler, Prof. Asya Rolls, Dr. Nitzan Lubianiker, and Dr. Tamar Koren. “The ability to consciously activate brain mechanisms associated with positive anticipation opens a new avenue for research and future treatments — as a complement to existing medicine, not as a replacement. In the future, it may be possible to develop simple, noninvasive tools to help strengthen immune responses and enhance the effectiveness of medical treatments by relying on the brain’s natural capacity to influence the body. However, it is important to emphasize that activation of the reward system and its effect on immune response vary between individuals. Therefore, this approach cannot replace existing medical treatments, but may well serve as an additional supportive component.”