A Rare Discovery Sheds New Light on the Evolution of Flight

Research

A Rare Discovery Sheds New Light on the Evolution of Flight

A new study led by a researcher from the School of Zoology and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University examined dinosaur fossils preserved with their feathers and found that these dinosaurs had lost the ability to fly. According to the researchers, this is an extremely rare finding that offers a glimpse into the functioning of creatures that lived 160 million years ago, and their impact on the evolution of flight in dinosaurs and birds.

The research team: “This finding has broad significance, as it suggests that the development of flight throughout the evolution of dinosaurs and birds was far more complex than previously believed. In fact, certain species may have developed basic flight abilities — and then lost them later in their evolution.”

The study was led by Dr. Yosef Kiat of the School of Zoology and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University, in collaboration with researchers from China and the United States. The article was published in Communications Biology, published by Nature Portfolio.

Dr. Kiat, an ornithologist specializing in feather research, explains: “The dinosaur lineage split from other reptiles 240 million years ago. Soon afterwards (on an evolutionary timescale) many dinosaurs developed feathers — a unique lightweight and strong organic structure, made of protein and used mainly for flight and for preserving body temperature. Around 175 million years ago, a lineage of feathered dinosaurs called Pennaraptora emerged - the distant ancestors of modern birds and the only lineage of dinosaurs to survive the mass extinction that marked the end of the Mesozoic era 66 million years ago. As far as we know, the Pennaraptora group developed feathers for flight, but it is possible that when environmental conditions changed, some of these dinosaurs lost their flight ability — just like the ostriches and penguins of today.”

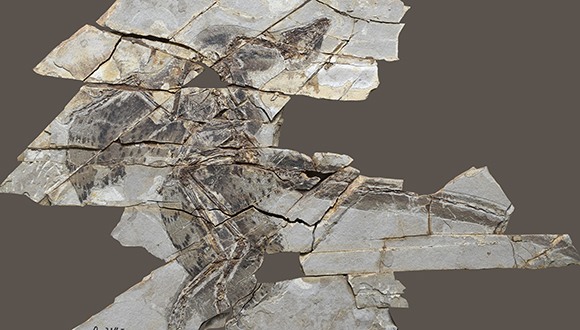

160-million-year-old Anchiornis fossils

In the study, nine fossils from eastern China were examined, all belonging to a feathered Pennaraptoran dinosaur taxon called Anchiornis. A rare paleontological finding, these fossils (and several hundred similar ones) were preserved with their feathers intact, thanks to the special conditions prevailing in the region during fossilization. Specifically, the nine fossils examined in the study were chosen because they had retained the color of the wing feathers — white with a black spot at the tip.

Here is where feather researcher Dr. Kiat enters the picture, explaining: “Feathers grow for two to three weeks. Reaching their final size, they detach from the blood vessels that fed them during growth and become dead material. Worn over time, they are shed and replaced by new feathers - in a process called molting, which tells an important story: birds that depend on flight, and thus on the feathers enabling them to fly, molt in an orderly, gradual process that maintains symmetry between the wings and allows them to keep flying during molting. In birds without flight ability, on the other hand, molting is more random and irregular. Consequently, the molting pattern tells us whether a certain winged creature was capable of flight.”

The preserved feather coloration in the dinosaur fossils from China allowed the researchers to identify the wing structure, with the edge featuring a continual line of black spots. Moreover, they were able to distinguish new feathers that had not yet completed their growth — since their black spots deviated from the black line. A thorough inspection of the new feathers in the nine fossils revealed that molting had not occurred in an orderly process.

Dr. Yosef Kiat of the School of Zoology and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History

Dr. Kiat: “Based on my familiarity with modern birds, I identified a molting pattern indicating that these dinosaurs were probably flightless. This is a rare and especially exciting finding: the preserved coloration of the feathers gave us a unique opportunity to identify a functional trait of these ancient creatures - not only the body structure preserved in fossils of skeletons and bones.”

Dr. Kiat concludes: “Feather molting seems like a small technical detail — but when examined in fossils, it can change everything we thought about the origins of flight. Anchiornis now joins the list of dinosaurs that were covered in feathers but not capable of flight, highlighting how complex and diverse wing evolution truly was.”

Research

Joint study by Tel Aviv University, the IDF Medical Corps, and the U.S. Department of Defense confirms and strengthens earlier findings

A joint study by Tel Aviv University, the IDF Medical Corps, and the U.S. Department of Defense has found that a series of specialized computer-based training exercises can significantly reduce the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among IDF combat soldiers. The new study confirmed and extends similar results obtained in a comparable trial conducted in 2012. Unfortunately, the program that was created as a result of this earlier study and implemented by the IDF in 2018 was shut down shortly before the outbreak of the Iron Swords War following budget cuts and restructuring in the army’s Mental Health Department.

The new study, involving 500+ soldiers from one of the IDF’s regular infantry brigades, was conducted in 2022–2023 (before the outbreak of the war) under the leadership of Prof. Yair Bar-Haim, Director of the National Center for Traumatic Stress and Resilience and member of the School of Psychological Sciences at Tel Aviv University, together with doctoral student Chelsea Gober Dykan. The results now appear in the American Journal of Psychiatry, one of the world’s leading journals in the field.

Prof. Bar-Haim explains that the computer-based training involves a simple task in which soldiers are shown both neutral and threatening images or words that are replaced by target shapes that appear on the screen near those stimuli. The soldiers are asked to identify the targets, a process that gradually trains them to direct more attention toward potential threats in their environment. Each session lasts about ten minutes and is completed individually, four times over separate days.

The earlier study, conducted in 2012, tested the effectiveness of the training among roughly 800 soldiers in one of the IDF’s infantry brigades. The soldiers completed the computerized training during basic training. In the summer of 2014, during Israel’s Operation Protective Edge, most of those soldiers saw combat. Four months after the fighting ended, Prof. Bar-Haim and his team found that 7.8% of the soldiers who had not received the training were diagnosed with PTSD, compared with just 2.6% among those who completed the training program.

Prof. Bar-Haim, Chelsea Gober Dykan, and their research team recently set out to replicate the earlier findings and reevaluate the training’s effectiveness, this time using slightly modified computer-based protocols. This study was conducted in 2022–2023 (before the outbreak of the Iron Swords War) at the brigade training base during advanced training. One-third of the soldiers received the original attentional training protocol, another third underwent a revised attentional training protocol, and the remaining third received placebo training. After completing their training, the soldiers were deployed on their first operational rotation in Judea and Samaria. Upon their return, the researchers assessed the impact of the different training protocols on the soldiers’ risk for developing PTSD.

The results were once again clear-cut. Among soldiers in the control (placebo) group, 5.3% reported clinically significant post-traumatic symptoms, compared to 2.7% in the group that received the revised attention-training protocol, and less than one percent (0.9%) among those who completed the original attention training version. The results show that the original protocol remained the most effective in reducing the risk of PTSD, while the revised method demonstrated lower efficacy.

“Replication of findings is a critical component of clinical science and provides confidence in the validity of results,” explains Prof. Bar-Haim. “We once again found that the attentional training we developed is effective in reducing the risk of PTSD among soldiers deployed on operational settings, which further strengthens our confidence in its impact - that’s the good news. However, we also saw that the additional method we tested, based on eye-tracking technology, proved to be less effective. That’s how it is in science: our hypotheses don’t always hold up under rigorous testing, and we therefore must draw conclusions accordingly and refine our tools through further research.”

Prof. Yair Bar-Haim, Head of the National Center for Traumatic Stress and Resilience

Prof. Bar-Haim notes that the less encouraging news is that the program was discontinued several months before the outbreak of the war, and thus was not available in its most potent and tested form to soldiers heading into the Gaza and Lebanon campaigns. To still provide some form of support ahead of the ground maneuvers in Gaza and Lebanon, the researchers, together with the IDF, developed a mobile application that allows soldiers to complete the training on their personal phones rather than at designated computer stations. The app, called “Combat Attention” (Keshev Kravi), was distributed to both regular forces and reservists prior to the start of the ground operation.

According to Prof. Bar-Haim, the new findings not only reinforce confidence in attentional training as an effective tool for building resilience and preventing PTSD among combat soldiers, but also can serve as a wake-up call to military decision-makers to reinstate the program at brigade training bases and expand its use across combat units.

Prof. Bar-Haim concludes: “The study was conducted before the war when soldiers’ operational activities where typical to the low-intensity combat experiences at that time. The results demonstrated significant differences in PTSD risk between soldiers who underwent the computer-based training and those who did not, rendering the program valuable during routine deployments. It is likely that in wartime, these gaps become even more pronounced, making attentional training even more desirable. During wartime, armies typically reach their peak operational capabilities, and the same often holds true for mental health care and prevention efforts. Now, as the war subsides, the greatest challenge for the IDF is to preserve and sustain these hard-won capabilities, ensuring they are not lost in quieter times when their importance may seem less urgent. Decision-makers are urged to act now to allocate the necessary budgets and design long-term evidence-based solutions for PTSD prevention and mitigation among deploying troops.