New research reveals that tipping is driven more by social conformity than genuine appreciation, offering only weak motivation for better service, yet pushing tipping rates ever higher.

Research

New research reveals that tipping is driven more by social conformity than genuine appreciation, offering only weak motivation for better service, yet pushing tipping rates ever higher.

What makes us tip? A new study explores two main motives: genuine appreciation for the service and conformity with social norms. Those who truly value the service tend to tip above the standard rate, while conformists usually align with them — leading to a gradual rise in average tipping rates over time.

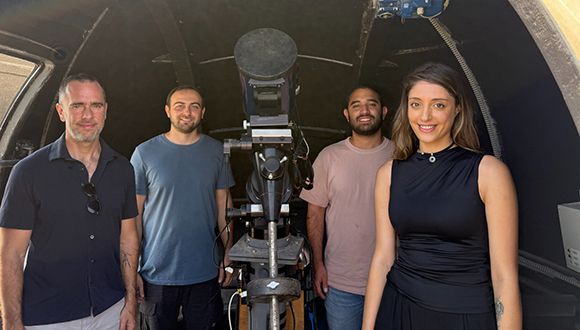

The study, published in Management Science, was conducted by Dr. Ran Snitkovsky of the Coller School of Management at Tel Aviv University, together with Prof. Laurens Debo of the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth College. Their theoretical model sheds light on the complexity of tipping and its economic and social implications.

“Tipping is a phenomenon that is difficult to explain using classical economic tools,” explains Dr. Snitkovsky. “The 'homo economicus', who is only interested in their own material wealth, has no reason to tip once the service has been provided.”

He adds that earlier research suggested tipping ensures better service in the future — but this doesn’t explain why people tip even when they are unlikely to meet the same service provider again, such as a taxi driver abroad. “Another common argument is that tipping provides an incentive for servers to give better service. Whether this is true or not, a self-interested customer would prefer others to tip and maintain good service quality while avoiding the expense himself. The conclusion is that to understand this phenomenon in depth, we must examine psychological and behavioral considerations.”

A recent study reported by USA Today revealed that the average American spends nearly $500 annually on tips in restaurants and bars, and that the tipping system in the U.S. generates over $50 billion each year, providing a primary source of income for millions of servers.

“We used a mathematical model and tools from game theory and behavioral economics to understand the motivations behind tipping,” says Dr. Snitkovsky. “Into this model we fed the two main reasons people report for tipping: the first is to express gratitude to the service provider, and the second is conformity —doing what everybody else does.”

“The first reason relates to my personal valuation of the service I received or the server-customer interaction, and can stem from wanting to reward the server for doing their job or showing empathy towards them,” he continues. “The second reason is tied to how I perceive myself in society — my interaction with other customers. In other words, we can distinguish between ‘appreciators’ and ‘conformists’.”

The researchers found that in societies with stronger social pressure, where people feel a greater need to comply with the norm, average tip amounts tend to rise over time.

Dr. Ran Snitkovsky, Photo credit: Israel Hadari, Tel Aviv University

“The process is inherently driven by appreciators pulling the conformists upward, but not the other way around,” says Dr. Snitkovsky. “This might explain why tipping rates in the U.S. few decades ago were around 10% and are now closer to 20%. Those who appreciate the service are willing to tip well above the average, while those who wish to comply with the customary practice ‘chase’ the average. Additionally, rising tipping rates may also reflect growing economic inequality — a hypothesis proposed by another researcher from Tel Aviv University, Prof. Yoram Margalioth of the Buchmann Faculty of Law, and supported by our model.”

The study also explored whether tipping provides an effective incentive for servers to improve their performance. The model shows that while tips can encourage servers to exert effort, it is a relatively weak motivator, since many customers are conformists who will tip the standard amount in any case.

“If a server knows most customers are conformists, there’s little reason to put in extra effort since they will tip the customary amount anyway,” explains Dr. Snitkovsky. “This is indeed the situation in countries like the U.S.”

“In an imaginary world where all customers are appreciators, unaffected by each other's tipping rates, tipping would serve as a much stronger incentive. On the other hand, in such a world where tips only reflect appreciation, businesses might conclude that customers are willing to pay more for the service experience and charge higher prices upfront. This may trigger customers to adjust their expectations and reduce the tip percentage accordingly.”

The researchers also examined the 'tip credit' regulation applied in most U.S. states. This law allows employers to pay less than the minimum wage for tipped professions, covering the difference with tips. For instance, if the minimum wage is $8 per hour and the state has set the sub-minimum wage at $3, employers may pay servers only $3 and use tips to cover the $5 difference. Only if tips fall short of the minimum wage are employers required to make up the gap. If a server makes more than $8 after tips, they can keep the difference.

“We see that a higher tip credit allows businesses to reduce prices — because they rely more on tips to finance labor," says Dr. Snitkovsky. "Consequently, they can increase supply and serve more customers. This suggests an element of economic efficiency, but the efficiency in this case comes at the expense of the individual server's earnings. So essentially, tip credit is a mechanism allowing employers to cut into tips that ostensibly belong to servers, using them to pay wages.”

As for his personal view, Dr. Snitkovsky admits he dislikes tipping. “I came to this study with a bias. Personally, I don’t like this practice, and I wanted to understand what drives it. First of all, tipping puts customers in an uncomfortable position. Studies have shown that tipping can encourage sexist behavior toward female servers - who may refrain from setting boundaries to avoid losing tips. Other studies demonstrate that people tend to tip more generously when a server is of their own ethnicity, introducing an element of racism. It’s easy to find good reasons to do away tipping, but the custom also has some positive effects, making it a complex phenomenon.”

He adds: “Ultimately, tipping allows those willing to pay more for the service to do so, thereby subsidizing the service for others. That’s a positive aspect. Additionally, tips do seem to encourage servers to provide better service, even though this effect is very limited. In my opinion, in the 21st century business owners have better tools to assess server performance, such as online reviews and even in-house cameras.”

Research

TAU researchers reveal how fruit bats adjust their behavior, from caution to confrontation, in the competition for food.

A new study from the School of Zoology at Tel Aviv University reveals that fruit bats employ a variety of strategies in their competition with other animals for food. The research team examined bat behavior in the presence of black rats, which vie for the same food sources. They found that the bats’ behavior changes with the seasons and food availability: in winter, bats tend to avoid and act cautiously toward rats, while in summer, when competition is more intense, the bats are sometimes not afraid to engage in conflict — even at the risk of injury. The researchers note that the study, conducted over seven months and documented in a semi-natural bat colony, provides a rare glimpse into the way animals balance the dangers of predation with the need to compete for resources.

The research was conducted by the laboratory team of Prof. Yossi Yovel at Tel Aviv University’s School of Zoology, Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, author of The Genius Bat. It was led by PhD students Xing Chen and Adi Rachum, with the assistance of Liraz Attia and Dr. Lee Harten. The findings were published in the journal BMC Biology.

Prof. Yovel explains that over the course of hundreds of hours of video documentation, more than 150,000 bat landings near a food source were analyzed. The researchers found that when rats were present, the number of bats’ landings dropped dramatically due to fear of confrontation and rat attacks. In addition to competing for food, rats are known to prey on bats, especially on young bats. The bats that did land near food sources displayed heightened vigilance — pausing to scan their surroundings for long periods before approaching the food. This reduced their success in obtaining food by about 20%. Moreover, in some cases rats were observed attacking landing bats, underscoring the real threat they pose.

Prof. Yossi Yovel

“We learned that the interactions between bats and rats are diverse and vary with the seasons, depending on food availability,” says Prof. Yovel. “In winter, when rats were relatively scarce, the bats behaved more cautiously — they avoided landings and showed constant vigilance. In contrast, in spring, with the sharp increase in food abundance (which also meant more encounters with rats), the situation changed, and the bats sometimes even attacked the rats. This behavior apparently improved their foraging success rate, which rose to 60% in summer compared to only 35% in winter.”

Prof. Yovel concludes: “We tend to describe relationships between different species in simplistic terms — either as competition or predation. This study shows how complex such relationships can be and how animals are able to adapt their response strategies to changing circumstances. Because observations in nature are scarce, this complexity is usually difficult to quantify. What we achieved in this study therefore provides another example of the adaptability and intricate lives of wild animals in urban environments.”

Research

TAU researchers conduct Israel’s first ecological–biotechnological seaweed survey, revealing a natural hotspot of resilient, nutrient-rich species.

A team of researchers from Tel Aviv University and the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute (IOLR) has conducted the first comprehensive ecological–biotechnological seaweed survey in Israel. Their findings suggest that the unique ecological conditions along the Israeli Mediterranean coast—warm, sunny, and dynamic—create a natural habitat that supports the growth of distinctive and resilient seaweeds (macroalgae) rich in nutritional and health-promoting compounds. The researchers believe these properties could serve as a foundation for groundbreaking innovations in food, health, and biotechnology.

Tel Aviv University researchers have completed Israel’s first ecological–biotechnological seaweed survey, uncovering a natural “green treasure” growing along the country’s Mediterranean coast. Their findings reveal that the region’s warm, sunny, and dynamic conditions nurture exceptional seaweeds rich in nutritional, medicinal, and biotechnological potential — from sustainable superfoods to eco-friendly cosmetics and pharmaceutical innovations.

The pioneering study, led by Dr. Doron Yehoshua Ashkenazi of Tel Aviv University and the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research Institute (IOLR), was conducted under the supervision of Prof. Avigdor Abelson from TAU’s School of Zoology and Prof. Álvaro Israel from IOLR Haifa, in collaboration with Dr. Eitan Salomon of the National Center for Mariculture in Eilat.

Additional contributors included Prof. Félix L. Figueroa and Dr. Julia Vega of the University of Málaga, Spain, Guy Paz, head of the laboratory at IOLR, and Dr. Shoshana Ben-Valid. The study was published in Marine Drugs.

Over several years, the researchers collected nearly 400 specimens, identifying 55 seaweed species—predominantly red, alongside brown and green seaweeds. In contrast to earlier reports suggesting two annual peaks in seaweed productivity, this study indicates a single productive period in springtime, strongly suggesting an ecosystem shift likely driven by global warming.

Seasonal analysis revealed dramatic biochemical differences. During winter, local seaweeds reached exceptionally high protein levels — several tens of percent of their dry weight — making them a promising alternative protein source for both human and animal consumption.

In spring, antioxidant compounds surged by nearly 300% in some species, positioning these seaweeds as a potent source of health-promoting and anti-aging compounds.

High concentrations of phenolic compounds and natural UV filters also highlight their potential for eco-friendly cosmetics and therapeutic uses.

"Israel, located at the easternmost edge of the Mediterranean Sea, offers unique environmental conditions,” Dr. Doron Ashkenazi explains. “a subtropical climate with year-round sunlight, rocky shores with small tidal fluctuations, and relatively high salinity and irradiance. Together, these factors stimulate the development of seaweeds with unique chemical traits that act as natural ‘biological factories,’ producing bioactive compounds in remarkable concentrations.”

He adds: "We believe that this study, together with the growing seaweed research field, can place Israel at the forefront of global marine biotechnology. In addition to being ‘a land flowing with milk and honey,’ Israel has also been blessed with a unique and life-giving sea — the Israeli Mediterranean.”

Prof. Álvaro Israel emphasizes: "This study provides valuable insights into the environmental factors that influence seaweed growth and quality, allowing us to translate this knowledge into practical aquaculture methods. Seaweed offers immense environmental benefits—they require no arable land, generate oxygen, capture carbon, and purify water from pollutants. They stand at the forefront of sustainable aquaculture, merging environmental advantages with economic opportunities.

Dr. Eitan Salomon adds: “Our findings illustrate the untapped biotechnological potential of seaweeds for the future of humanity – from functional foods and pharmaceuticals to a variety of advanced health applications.”

Prof. Avigdor Abelson concludes: “The Israeli Mediterranean Sea is a unique natural laboratory. It can serve as a model for understanding the impacts of climate change on marine ecosystems and help predict which species may thrive in a warming world. Beyond its scientific value, seaweeds represent a strategic national and global resource that can help address future challenges in food security, health, and the environment.”

Research

TAU researchers discover how to increase myelin production — a finding that could aid treatments for Alzheimer’s and multiple sclerosis.

Researchers from Tel Aviv University have discovered a new biological mechanism that enhances the production of myelin — a substance essential for proper brain function and nerve communication. “Our findings may serve as the basis for developing innovative treatments for severe neurological disorders involving myelin damage, including multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and certain neurodevelopmental syndromes,” the researchers note.

The study was conducted in the laboratory of Prof. Boaz Barak of the Sagol School of Neuroscience and the School of Psychological Sciences at Tel Aviv University and led by Dr. Gilad Levy. The lab collaborated with researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Weizmann Institute of Science, Tel Aviv University, and Germany’s Max Planck Institute. The findings were published in Nature Communications.

Prof. Barak explains: “Damage to myelin is associated with a variety of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis (an autoimmune disease in which the body itself attacks the myelin), as well as neurodevelopmental syndromes like Williams syndrome and autism spectrum disorders. In this study we focused on the cells that produce myelin in both the central and peripheral nervous systems. Specifically in these cells, we investigated the role of a protein called Tfii-i, known for its ability to increase or decrease the expression of many genes crucial for cell function. While Tfii-i has long been linked to abnormal brain development and neurodevelopmental syndromes, its role in myelin production had not been studied until now.”

Prof. Barak's team discovered that the Tfii-i acts as a 'biological brake' that inhibits myelin production in the relevant cells. Based on this finding, the researchers hypothesized that reducing Tfii-i activity in myelinating cells might increase myelin output.

Prof. Boaz Barak

To test this, the team used advanced genetic engineering in model mice: Tfii-i expression was selectively eliminated only in myelin-producing cells, while remaining unchanged in all other cells. These genetically modified mice were compared to normal mice in a wide variety of measures, including levels of myelin proteins, structure and thickness of the myelin sheath surrounding axons, speed of nerve signal conduction, and even motor and behavioral performance.

Dr. Gilad Levy explains: “We found that in the absence of Tfii-i, the myelin-producing cells generated higher amounts of myelin proteins. This resulted in abnormally thick myelin sheaths, which enhanced the conduction speed of electrical signals along the neural axons. These improvements resulted in a significant enhancement of the mice’s motor abilities, including better coordination and mobility, along with other behavioral benefits.”

Prof. Barak concludes: “In this study we demonstrated for the first time that it is possible to ‘release the brakes’ on myelin production in the brain and peripheral nervous system by regulating the expression of Tfii-i. This study is among the few to identify a mechanism for increasing myelin levels in the brain. Its results may enable the development of future therapies that suppress Tfii-i activity in myelin-producing cells, to restore myelin in a wide variety of degenerative and developmental diseases in which myelin is impaired — including Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, Williams syndrome, and autism spectrum disorders. We believe this fundamentally new approach holds great therapeutic potential.”

Research

A new TAU study offers the first strong evidence that most massive stars in the early universe formed as binary systems — pairs of stars orbiting closely together.

A study led by Dr. Tomer Shenar from TAU’s School of Physics and Astronomy, Dr. Hugues Sana of KU Leuven University in Belgium, and Dr. Julia Bodensteiner of the University of Amsterdam reveals that the earliest massive stars were likely born in pairs, similar to those seen in our own galaxy. The findings were published in Nature Astronomy.

The researchers estimate that this discovery provides the first convincing evidence that massive binary stars were common in the early universe. Such systems, they explain, influence the universe on many scales — from forming black holes of all sizes, to powering energetic supernovae, and enriching galaxies with the elements that make life possible.

The researchers explain that massive stars, those with at least ten times the mass of the Sun, are responsible for a variety of cosmic phenomena. A single massive star can emit more energy energy than a million Sun-like stars. Massive stars shape the structure and properties of their host galaxies, produce most of the universe’s heavy elements, and end their lives in powerful supernova explosions, leaving behind the most mysterious objects we know: neutron stars and black holes.

In our galaxy, the Milky Way, it is well established that most massive stars are born in “binary systems”, pairs of stars in orbits so close that they exchange matter and sometimes even merge during their lifetimes. These interactions fundamentally alter the evolution and fate of the massive stars.

Massive stars — those with at least ten times the mass of our Sun — drive many of the universe’s most powerful phenomena. A single massive star can emit more energy than a million sun-like stars. They shape galaxies, create heavy elements, and end their lives in supernova explosions that leave behind neutron stars or black holes.

In our Milky Way, it is well established that most massive stars form in binary systems, orbiting so closely that they exchange matter and sometimes even merge. These interactions profoundly affect how such stars evolve and die.

A key question is whether this “binarity” also characterized the massive stars that formed shortly after the Big Bang. The James Webb Space Telescope has detected early galaxies filled with massive stars, but their great distance makes it impossible to directly study their stellar systems.

Dr. Shenar explains: “To overcome this limitation, we developed an observational survey designed to study massive stars in a relatively nearby galaxy that mimics the chemical conditions of the early universe. As part of the survey Binarity at LOw Metallicity (BLOeM), we carried out a two-year observing campaign with the VLT in Chile, during which we obtained spectra of about 1,000 massive stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud—a neighboring galaxy with a low metal content, resembling the composition of the young universe.”

Dr. Shenar adds: “Spectral analysis of the data enables measurement of periodic motions of stars, thereby revealing the presence of stellar companions. From detailed analysis of 150 of the most massive stars, we found that at least 70% are part of close binary systems. This constitutes the first direct and convincing evidence that massive stars commonly existed in binaries even under the conditions of the early universe, perhaps even more frequently than today.”

The team concludes that these results change our understanding of how the universe evolved — from the formation of black holes and the nature of supernova explosions, to the enrichment of galaxies with heavy elements essential for the formation of stars, planets, and life itself.

Research

A new TAU study predicts that radio waves from the cosmic dark ages can help uncover the properties of dark matter, offering astrophysicists a new observational tool.

A new study from Tel Aviv University has predicted, for the first time, the groundbreaking results that can be obtained from detecting radio waves coming to us from the early Universe. The findings show that during the cosmic dark ages, dark matter formed dense clumps throughout the Universe, which pulled in hydrogen gas and caused it to emit intense radio waves. This leads to a novel method to use the measured radio signals to help resolve the mystery of dark matter.

The study was led by Prof. Rennan Barkana from Tel Aviv University’s Sackler School of Physics and Astronomy and included his Ph.D. student Sudipta Sikder as well as collaborators from Japan, India, and the UK. Their novel conclusions have been published in the prestigious journal Nature Astronomy.

The researchers note that the cosmic dark ages (the period just before the formation of the first stars) can be studied by detecting radio waves that were emitted from the hydrogen gas that filled the Universe at that time. While a simple TV antenna can detect radio waves, the specific waves from the early Universe are blocked by the Earth’s atmosphere. They can only be studied from space, particularly the moon, which offers a stable environment, free of any interference from the Earth’s atmosphere or from radio communications. Of course, putting a telescope on the moon is no simple matter, but we are seeing an international space race in which many countries are trying to return to the moon with space probes and, eventually, astronauts. Space agencies in the U.S., Europe, China and India are searching for worthy scientific goals for lunar development, and the new research highlights the potential of detecting radio waves from the cosmic dark ages.

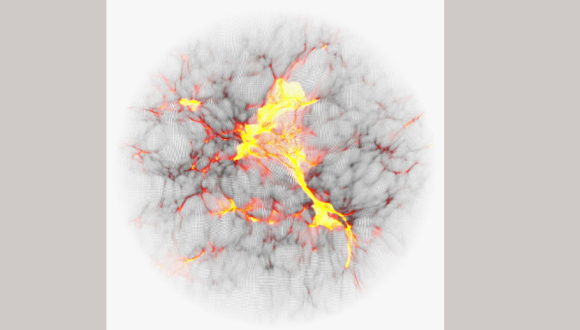

Colored computer simulation showing the temperature map of cosmic gas.

Prof. Barkana explains: “NASA’s new James Webb space telescope discovered recently distant galaxies whose light we receive from early galaxies, around 300 million years after the Big Bang. Our new research studies an even earlier and more mysterious era: the cosmic dark ages, only 100 million years after the Big Bang. Computer simulations predict that dark matter throughout the Universe was forming dense clumps, which would later help form the first stars and galaxies. The predicted size of these nuggets depends on, and thus can help illuminate, the unknown properties of dark matter, but they cannot be seen directly. However, these dark matter clumps pulled in hydrogen gas and caused it to emit stronger radio waves. We predict that the cumulative effect of all this can be detected with radio antennas that measure the average radio intensity on the sky.”

This radio signal from the cosmic dark ages should be relatively weak, but if the observational challenges can be overcome, it will open new avenues for testing the nature of dark matter. When the first stars formed a short time later, in the period known as cosmic dawn, their starlight is predicted to have strongly amplified the radio wave signal. The signal from this later era should be easier to observe, and this can be done using telescopes on Earth, but the radio measurements will be more challenging to interpret, given the influence of star formation with all of its complexity. In this case, though, a great deal of complementary information is potentially available from large radio telescope arrays that will attempt to produce a complete map of the radio waves on the sky, looking for patterns of strong and weak emission that should also reveal the presence of the same dark matter clumps. Prof. Barkana is part of the largest such international collaboration, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), which includes a massive array of 80,000 radio antennas currently being rolled out in Australia.

The researchers assess that the findings may be very significant for the scientific understanding of dark matter. In the present Universe, dark matter has had billions of years to interact with stars and galaxies, making it more difficult to decode its properties. In contrast, the pristine conditions in the early Universe offer a potentially perfect laboratory for astrophysicists.

Prof. Barkana concludes: “Just as old radio stations are being replaced with newer technology that brings forth websites and podcasts, astronomers are expanding the reach of radio astronomy. When scientists open a new observational window, surprising discoveries usually result. The holy grail of physics is to discover the properties of dark matter, the mysterious substance that we know constitutes most of the matter in the Universe, yet we do not know much about its nature and properties. Understandably, astronomers are eager to start tuning into the cosmic radio channels of the early Universe.”

Research

TAU study demonstrates how muon detectors can be used to map subterranean voids before excavation, offering archaeologists a powerful new tool.

A technological breakthrough at Tel Aviv University offers archaeologists a way to identify underground spaces before digging. The system detects muons — elementary particles generated when cosmic rays hit Earth’s atmosphere — which can penetrate rock and soil up to 100 meters deep. By tracking their paths, researchers can locate hidden voids such as tunnels and cisterns.

The method was successfully demonstrated at the City of David archaeological site in Jerusalem, where the system mapped Jeremiah’s Cistern by identifying changes in soil permeability to muons.

The study was led by Prof. Erez Etzion from TAU's Raymond and Beverly Sackler School of Physics and Astronomy, and Prof. Oded Lipschits from TAU's Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures. Other participants included: Prof. Yuval Gadot from the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures; Prof. Yan Benhammou, Dr. Igor Zolkin, and doctoral student Gilad Mizrachi from the School of Physics and Astronomy; Dr. Yiftah Silver and Dr. Amir Weissbein of Rafael Advanced Defense Systems; and Dr. Yiftah Shalev of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The study's results were published in the Journal of Applied Physics.

“From the pyramids in Egypt, through the Maya cities in South America, to ancient sites in Israel, archaeologists struggle to discover underground spaces,” explains Prof. Lipschits. “Above-ground structures are relatively easy to excavate, and there are also various methods for identifying walls and structures below the surface. However, there are no effective methods for conducting comprehensive surveys of subterranean spaces beneath the rock on which the ancient site is situated. In the Judean Foothills, for example, the top layer of hard limestone overlies soft chalk, in which the ancients easily carved out vast spaces for water reservoirs, agricultural uses, storage, or even dwellings. Clearly, in such regions, most above-ground archaeological sites resemble Swiss cheese beneath the rock, but we have no way of knowing this. If by chance we excavate above ground, reach the rock, and identify an entrance to a cavity, we could excavate it, but we have no way of locating the subterranean spaces in advance. In the current study, we propose for the first time an innovative method that has been proven very effective in detecting underground spaces with detectors of cosmic radiation, specifically muons.”

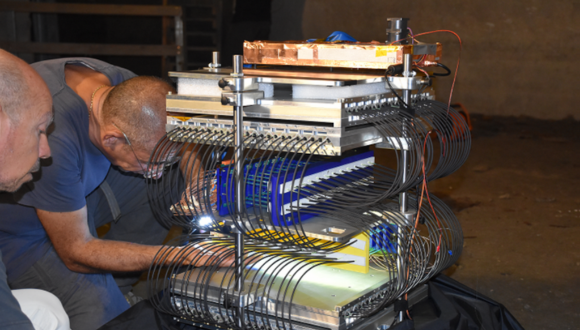

A team from TAU is installing the muon detectors in Jeremiah’s Cave beneath the City of David site

The researchers explain that a muon is an elementary particle similar to an electron but 207 times more massive. Muons are created in the atmosphere when energetic particles, mainly protons, collide with the nuclei of molecules in the air. This collision generates unstable particles called pions, which decay very quickly into muons. Muons also have a very short lifetime, decaying after 2.2 microseconds, but they move at speeds close to the speed of light, and thanks to Einstein’s special relativity theory, many of them manage to reach and penetrate the ground.

“The muon shower hits the ground at a fixed and known rate,” explains Prof. Etzion. “Unlike electrons, which are stopped by the ground at just a few centimeters deep, muons lose energy slowly as they pass through the ground, and some can penetrate much deeper – even up to 100 meters for highly energetic particles. Therefore, by placing muon detectors underground and monitoring the environment, we can identify empty cavities where energy loss is minimal. This process is similar to X-ray imaging: the X-ray beam is stopped by bones but passes through soft tissue like flesh or fat, and a camera on the other side captures the resulting image. In our case, the muons act as the X-ray beam, our detector is the camera, and the underground features are the human body.”

As noted, the researchers conducted an impressive demonstration in a rock-hewn installation known as Jeremiah’s Cistern at the archaeological site of the City of David. Combining a high-resolution LiDAR scan of the interior cavity with simulations of the muon flux, they were able to map structural anomalies. Detecting changes in soil penetrability to muons, the system demonstrated the feasibility of using muon tomography for archaeological imaging.

“This article is a first milestone,” says Prof. Lipschits. “We ask physicists to respond to the archaeological need and develop smaller, simpler, cheaper, more durable, more accurate, and more power-efficient detectors. In the next stage, we intend to combine physics and archaeology with AI to produce a 3D image of the subsurface from the vast data generated by the detectors. Our test site will be Tel Azekah in the heart of the Judean Foothills, overlooking the Elah Valley.”

“This is not our invention,” adds Prof. Etzion. “Already in the 1960s, muons were used to search for hidden chambers in the pyramids in Egypt, and recently the technology was revived. Our innovation lies in developing small and mobile detectors and learning how to operate them at archaeological sites. After all, there is a difference between a detector in laboratory conditions and a detector that must be taken to a cave or excavation, where practical problems of electricity, temperature, and humidity inevitably arise. Detection ranges depend on measuring time; the farther the detector's location, the fewer particles reach it, but realistically, it is possible to analyze images from a distance of up to 30 meters within a reasonable timespan. Therefore, our goal is to place several detectors or move one detector from place to place to produce a 3D image of the entire site eventually. And we have just begun. The next stage involves sophisticated analysis, which will allow us to map everything beneath our feet – even before the excavation begins.”