A new TAU study offers the first strong evidence that most massive stars in the early universe formed as binary systems — pairs of stars orbiting closely together.

Research

A new TAU study offers the first strong evidence that most massive stars in the early universe formed as binary systems — pairs of stars orbiting closely together.

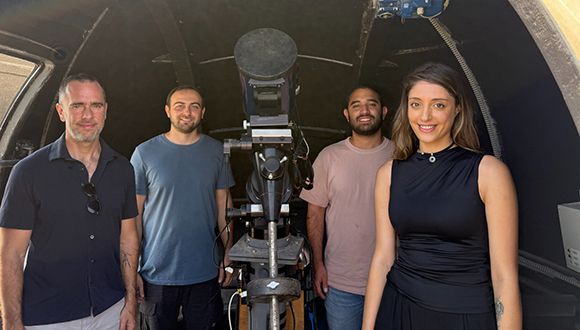

A study led by Dr. Tomer Shenar from TAU’s School of Physics and Astronomy, Dr. Hugues Sana of KU Leuven University in Belgium, and Dr. Julia Bodensteiner of the University of Amsterdam reveals that the earliest massive stars were likely born in pairs, similar to those seen in our own galaxy. The findings were published in Nature Astronomy.

The researchers estimate that this discovery provides the first convincing evidence that massive binary stars were common in the early universe. Such systems, they explain, influence the universe on many scales — from forming black holes of all sizes, to powering energetic supernovae, and enriching galaxies with the elements that make life possible.

The researchers explain that massive stars, those with at least ten times the mass of the Sun, are responsible for a variety of cosmic phenomena. A single massive star can emit more energy energy than a million Sun-like stars. Massive stars shape the structure and properties of their host galaxies, produce most of the universe’s heavy elements, and end their lives in powerful supernova explosions, leaving behind the most mysterious objects we know: neutron stars and black holes.

In our galaxy, the Milky Way, it is well established that most massive stars are born in “binary systems”, pairs of stars in orbits so close that they exchange matter and sometimes even merge during their lifetimes. These interactions fundamentally alter the evolution and fate of the massive stars.

Massive stars — those with at least ten times the mass of our Sun — drive many of the universe’s most powerful phenomena. A single massive star can emit more energy than a million sun-like stars. They shape galaxies, create heavy elements, and end their lives in supernova explosions that leave behind neutron stars or black holes.

In our Milky Way, it is well established that most massive stars form in binary systems, orbiting so closely that they exchange matter and sometimes even merge. These interactions profoundly affect how such stars evolve and die.

A key question is whether this “binarity” also characterized the massive stars that formed shortly after the Big Bang. The James Webb Space Telescope has detected early galaxies filled with massive stars, but their great distance makes it impossible to directly study their stellar systems.

Dr. Shenar explains: “To overcome this limitation, we developed an observational survey designed to study massive stars in a relatively nearby galaxy that mimics the chemical conditions of the early universe. As part of the survey Binarity at LOw Metallicity (BLOeM), we carried out a two-year observing campaign with the VLT in Chile, during which we obtained spectra of about 1,000 massive stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud—a neighboring galaxy with a low metal content, resembling the composition of the young universe.”

Dr. Shenar adds: “Spectral analysis of the data enables measurement of periodic motions of stars, thereby revealing the presence of stellar companions. From detailed analysis of 150 of the most massive stars, we found that at least 70% are part of close binary systems. This constitutes the first direct and convincing evidence that massive stars commonly existed in binaries even under the conditions of the early universe, perhaps even more frequently than today.”

The team concludes that these results change our understanding of how the universe evolved — from the formation of black holes and the nature of supernova explosions, to the enrichment of galaxies with heavy elements essential for the formation of stars, planets, and life itself.

Research

A new TAU study predicts that radio waves from the cosmic dark ages can help uncover the properties of dark matter, offering astrophysicists a new observational tool.

A new study from Tel Aviv University has predicted, for the first time, the groundbreaking results that can be obtained from detecting radio waves coming to us from the early Universe. The findings show that during the cosmic dark ages, dark matter formed dense clumps throughout the Universe, which pulled in hydrogen gas and caused it to emit intense radio waves. This leads to a novel method to use the measured radio signals to help resolve the mystery of dark matter.

The study was led by Prof. Rennan Barkana from Tel Aviv University’s Sackler School of Physics and Astronomy and included his Ph.D. student Sudipta Sikder as well as collaborators from Japan, India, and the UK. Their novel conclusions have been published in the prestigious journal Nature Astronomy.

The researchers note that the cosmic dark ages (the period just before the formation of the first stars) can be studied by detecting radio waves that were emitted from the hydrogen gas that filled the Universe at that time. While a simple TV antenna can detect radio waves, the specific waves from the early Universe are blocked by the Earth’s atmosphere. They can only be studied from space, particularly the moon, which offers a stable environment, free of any interference from the Earth’s atmosphere or from radio communications. Of course, putting a telescope on the moon is no simple matter, but we are seeing an international space race in which many countries are trying to return to the moon with space probes and, eventually, astronauts. Space agencies in the U.S., Europe, China and India are searching for worthy scientific goals for lunar development, and the new research highlights the potential of detecting radio waves from the cosmic dark ages.

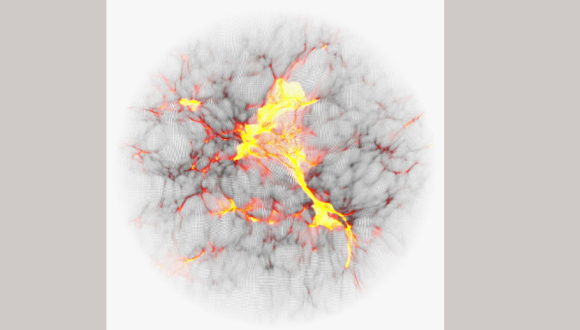

Colored computer simulation showing the temperature map of cosmic gas.

Prof. Barkana explains: “NASA’s new James Webb space telescope discovered recently distant galaxies whose light we receive from early galaxies, around 300 million years after the Big Bang. Our new research studies an even earlier and more mysterious era: the cosmic dark ages, only 100 million years after the Big Bang. Computer simulations predict that dark matter throughout the Universe was forming dense clumps, which would later help form the first stars and galaxies. The predicted size of these nuggets depends on, and thus can help illuminate, the unknown properties of dark matter, but they cannot be seen directly. However, these dark matter clumps pulled in hydrogen gas and caused it to emit stronger radio waves. We predict that the cumulative effect of all this can be detected with radio antennas that measure the average radio intensity on the sky.”

This radio signal from the cosmic dark ages should be relatively weak, but if the observational challenges can be overcome, it will open new avenues for testing the nature of dark matter. When the first stars formed a short time later, in the period known as cosmic dawn, their starlight is predicted to have strongly amplified the radio wave signal. The signal from this later era should be easier to observe, and this can be done using telescopes on Earth, but the radio measurements will be more challenging to interpret, given the influence of star formation with all of its complexity. In this case, though, a great deal of complementary information is potentially available from large radio telescope arrays that will attempt to produce a complete map of the radio waves on the sky, looking for patterns of strong and weak emission that should also reveal the presence of the same dark matter clumps. Prof. Barkana is part of the largest such international collaboration, the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), which includes a massive array of 80,000 radio antennas currently being rolled out in Australia.

The researchers assess that the findings may be very significant for the scientific understanding of dark matter. In the present Universe, dark matter has had billions of years to interact with stars and galaxies, making it more difficult to decode its properties. In contrast, the pristine conditions in the early Universe offer a potentially perfect laboratory for astrophysicists.

Prof. Barkana concludes: “Just as old radio stations are being replaced with newer technology that brings forth websites and podcasts, astronomers are expanding the reach of radio astronomy. When scientists open a new observational window, surprising discoveries usually result. The holy grail of physics is to discover the properties of dark matter, the mysterious substance that we know constitutes most of the matter in the Universe, yet we do not know much about its nature and properties. Understandably, astronomers are eager to start tuning into the cosmic radio channels of the early Universe.”

Research

TAU study demonstrates how muon detectors can be used to map subterranean voids before excavation, offering archaeologists a powerful new tool.

A technological breakthrough at Tel Aviv University offers archaeologists a way to identify underground spaces before digging. The system detects muons — elementary particles generated when cosmic rays hit Earth’s atmosphere — which can penetrate rock and soil up to 100 meters deep. By tracking their paths, researchers can locate hidden voids such as tunnels and cisterns.

The method was successfully demonstrated at the City of David archaeological site in Jerusalem, where the system mapped Jeremiah’s Cistern by identifying changes in soil permeability to muons.

The study was led by Prof. Erez Etzion from TAU's Raymond and Beverly Sackler School of Physics and Astronomy, and Prof. Oded Lipschits from TAU's Jacob M. Alkow Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures. Other participants included: Prof. Yuval Gadot from the Department of Archaeology and Ancient Near Eastern Cultures; Prof. Yan Benhammou, Dr. Igor Zolkin, and doctoral student Gilad Mizrachi from the School of Physics and Astronomy; Dr. Yiftah Silver and Dr. Amir Weissbein of Rafael Advanced Defense Systems; and Dr. Yiftah Shalev of the Israel Antiquities Authority. The study's results were published in the Journal of Applied Physics.

“From the pyramids in Egypt, through the Maya cities in South America, to ancient sites in Israel, archaeologists struggle to discover underground spaces,” explains Prof. Lipschits. “Above-ground structures are relatively easy to excavate, and there are also various methods for identifying walls and structures below the surface. However, there are no effective methods for conducting comprehensive surveys of subterranean spaces beneath the rock on which the ancient site is situated. In the Judean Foothills, for example, the top layer of hard limestone overlies soft chalk, in which the ancients easily carved out vast spaces for water reservoirs, agricultural uses, storage, or even dwellings. Clearly, in such regions, most above-ground archaeological sites resemble Swiss cheese beneath the rock, but we have no way of knowing this. If by chance we excavate above ground, reach the rock, and identify an entrance to a cavity, we could excavate it, but we have no way of locating the subterranean spaces in advance. In the current study, we propose for the first time an innovative method that has been proven very effective in detecting underground spaces with detectors of cosmic radiation, specifically muons.”

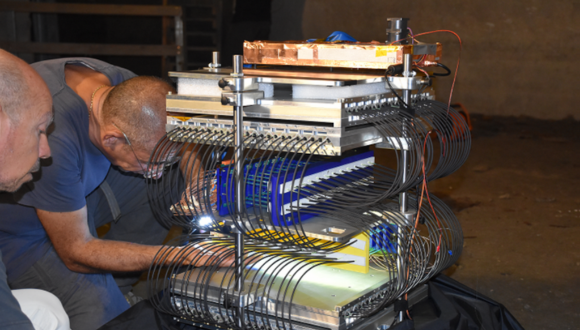

A team from TAU is installing the muon detectors in Jeremiah’s Cave beneath the City of David site

The researchers explain that a muon is an elementary particle similar to an electron but 207 times more massive. Muons are created in the atmosphere when energetic particles, mainly protons, collide with the nuclei of molecules in the air. This collision generates unstable particles called pions, which decay very quickly into muons. Muons also have a very short lifetime, decaying after 2.2 microseconds, but they move at speeds close to the speed of light, and thanks to Einstein’s special relativity theory, many of them manage to reach and penetrate the ground.

“The muon shower hits the ground at a fixed and known rate,” explains Prof. Etzion. “Unlike electrons, which are stopped by the ground at just a few centimeters deep, muons lose energy slowly as they pass through the ground, and some can penetrate much deeper – even up to 100 meters for highly energetic particles. Therefore, by placing muon detectors underground and monitoring the environment, we can identify empty cavities where energy loss is minimal. This process is similar to X-ray imaging: the X-ray beam is stopped by bones but passes through soft tissue like flesh or fat, and a camera on the other side captures the resulting image. In our case, the muons act as the X-ray beam, our detector is the camera, and the underground features are the human body.”

As noted, the researchers conducted an impressive demonstration in a rock-hewn installation known as Jeremiah’s Cistern at the archaeological site of the City of David. Combining a high-resolution LiDAR scan of the interior cavity with simulations of the muon flux, they were able to map structural anomalies. Detecting changes in soil penetrability to muons, the system demonstrated the feasibility of using muon tomography for archaeological imaging.

“This article is a first milestone,” says Prof. Lipschits. “We ask physicists to respond to the archaeological need and develop smaller, simpler, cheaper, more durable, more accurate, and more power-efficient detectors. In the next stage, we intend to combine physics and archaeology with AI to produce a 3D image of the subsurface from the vast data generated by the detectors. Our test site will be Tel Azekah in the heart of the Judean Foothills, overlooking the Elah Valley.”

“This is not our invention,” adds Prof. Etzion. “Already in the 1960s, muons were used to search for hidden chambers in the pyramids in Egypt, and recently the technology was revived. Our innovation lies in developing small and mobile detectors and learning how to operate them at archaeological sites. After all, there is a difference between a detector in laboratory conditions and a detector that must be taken to a cave or excavation, where practical problems of electricity, temperature, and humidity inevitably arise. Detection ranges depend on measuring time; the farther the detector's location, the fewer particles reach it, but realistically, it is possible to analyze images from a distance of up to 30 meters within a reasonable timespan. Therefore, our goal is to place several detectors or move one detector from place to place to produce a 3D image of the entire site eventually. And we have just begun. The next stage involves sophisticated analysis, which will allow us to map everything beneath our feet – even before the excavation begins.”

Research

A new study from Tel Aviv University and Dana Dwek Children’s Hospital shows that obese children can remain healthy if liver fat is kept low — highlighting diet quality as a key factor in preventing disease.

A study conducted at Tel Aviv University and Dana Dwek Children’s Hospital in Tel Aviv found that disease can be prevented in children with obesity by maintaining a low percentage of fat in the liver. The researchers used innovative methods to examine 31 Israeli children with obesity, in an attempt to understand why some have developed illnesses as a result of their excess weight — while others remain healthy (so far). They discovered that the percentage of fat in the livers of children already experiencing illness was two and a half times higher - 14% compared to 6% - than in the group of healthy obese children.

Quality Over QuantityThe researchers emphasize that, according to the findings, the health of obese children is influenced not only by the quantity, but also by the quality and composition of the food they eat. “The study indicates that even if obese children do not lose weight or reduce their food intake, their health can be protected by monitoring the components of their diet and minimizing fatty liver damage,”they explain.

The groundbreaking study was led by Prof. Yftach Gepner and doctoral student Ron Sternfeld from the Gray Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences and the Sylvan Adams Sports Science Institute at Tel Aviv University, together with Prof. Hadar Moran-Lev and Prof. Ronit Lubetzky from the Dana Dwek Children’s Hospital. The findings were published in the journal Frontiers in Nutrition.

Ron Sternfeld explains: “This is a cross-sectional study, which means we did not follow the children over time but rather examined them thoroughly at one point in time. Therefore, we can only indicate correlation, but not causality in our findings. Nonetheless, the study is important and unique, investigating why some obese children remain metabolically healthy, while others of the same weight already show signs of metabolic disease. To this end, we conducted a wide range of medical tests and reviewed the children’s medical records dating back to the prenatal stage. The highlight of the study was the use of MRS technology — an advanced non-invasive method that directly assesses liver composition, enabling precise measurement of liver fat percentage during MRI scans. This is one of the few studies ever to use MRS for diagnosing fatty liver in obese children.

To identify the best predictor of metabolic disease in obese children, the researchers examined 31 children treated at the Obesity Clinic of Dana Dwek's Gastroenterology Institute. The children were similar in age and body weight, but one group was still metabolically healthy while the other already showed abnormal rates of fasting glucose, blood lipids, cholesterol, and/or blood pressure. The researchers found that the factor most associated with metabolic illness was the percentage of fat in the liver: 14% in children already showing illness, compared to only 6% in the group of obese but still healthy children.

“We checked many different criteria and found no difference between the two groups,” says Ron Sternfeld. “For example, we found no difference in the visceral fat which surrounds internal organs in the abdomen, considered a major metabolic risk indicator. In contrast, a dramatic gap was found in the percentage of fat in the liver. Fatty liver is defined as a condition where more than 5.5% of the liver is composed of fat. Linked to diabetes, high blood pressure, sleep apnea, and more, fatty liver is considered one of the main causes of illness associated with obesity. To our surprise we found that some obese children do not have fatty liver.”

According to the researchers, this phenomenon is difficult to explain — although some hypotheses can be suggested. Prof. Gepner: “Comparing the children's diets, we found that those already ill consume higher levels of sodium, processed food, and certain saturated fatty acids from animal protein — mainly red meat. This means that the quality, not just the quantity of the food, plays a role. A Mediterranean diet may provide protection against metabolic illness, even in the case of obesity. Another possibility has to do with the children's medical history: we found that three times as many children in the ‘unhealthy obesity’ group, compared to those still healthy, had been born following high-risk pregnancies. Whatever the precise cause, our study strengthens the hypothesis that the liver is the most important metabolic organ and should be a primary target for preventive medicine.”

Research

TAU researchers have developed a targeted method of delivering locked nucleic acids (LNAs) using lipid nanoparticles, achieving therapeutic effect against inflammatory bowel disease in preclinical models — without side effects.

Researchers at Tel Aviv University have developed a new approach for using locked nucleic acids (LNAs) – a particularly stable type of RNA – to treat inflammatory bowel diseases such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. The researchers encapsulated selected LNA molecules, which silence a key gene in colitis, within lipid (fat) nanoparticles that serve as targeted drug carriers and injected the nanoparticles into colitis-model mice. The findings indicated improvement in all markers of systemic inflammation, with no side effects. According to the researchers, this innovative method may also be suitable for a wide range of other diseases – including rare genetic disorders, vascular and heart diseases, and neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s.

The study was conducted by the group of Prof. Dan Peer, a pioneer in the use of RNA molecules for therapy and vaccines, world expert in nanomedicine, and a senior faculty member at TAU's Shmunis School of Biomedicine and Cancer Research, Department of Materials Sciences and Engineering at the Fleischman Faculty of Engineering, Jan Koum Center for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology, and Cancer Biology Research Center. The group, led by Neubauer doctoral student Shahd Qassem together with Dr. Gonna Somu Naidu, a postdoctoral fellow who collaborated with researchers from F. Hoffman La-Roche (Roche) pharmaceutical company in Switzerland. The article was published in Nature Communications.

Prof. Peer explains: “Our study focused on unique RNA molecules called LNA. Unlike most RNA molecules, LNA molecules are very stable and do not break down easily. Consequently, until about 10 years ago, they were thought to have great potential as genetic drugs. However, experiments in laboratory animals, as well as clinical trials in humans (in chronic liver inflammation), showed that very large amounts of LNA are needed to achieve therapeutic efficacy. Moreover, administered by injection as a free drug, this high dosage proved very costly and caused severe side effects when spreading throughout the body. As a result, the effort to develop LNA-based drugs was abandoned. In our study we sought to test a new, better targeted and more effective approach.”

Prof. Dan Peer

The researchers used a method previously developed at Prof. Peer’s lab for other RNA molecules (such as siRNA, mRNA, circRNA), now applying it to LNA: they encapsulated the molecules in lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) that serve as targeted drug carriers, delivering their therapeutic payload directly to the relevant organ in the body. Specifically, they chose an LNA molecule known to silence the TNFα gene, which plays a significant role in inflammatory bowel diseases. Screening a lipid library developed in Prof. Peer’s lab over the past 13 years, they identified the most suitable lipid molecules and encapsulated the LNA molecules in them. The resulted LNPs were injected into mice in a model of chronic bowel diseases such as colitis.

The findings were highly encouraging: the dosage required to achieve the desired therapeutic effect was 30 times lower compared to past studies – in which LNA molecules were administered as a free drug without lipid encapsulation. At the current dosage, delivered precisely to the correct site, the drug proved highly effective in treating the disease, without causing any side effects.

Prof. Peer: “Our study paves the way to developing new LNA-based drugs for inflammatory bowel diseases, as well as a wide range of other diseases – including rare genetic disorders, vascular and heart diseases, and neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s and Huntington’s. So far, we have demonstrated that the new method is effective in chronic bowel inflammation in mice. We hope to proceed to clinical trials in humans in the near future.”

Research

A new TAU–Ichilov study shows that tracking eye movements can assess memory more accurately than verbal reports, with potential use for infants, Alzheimer’s patients, and brain injury victims.

Researchers from Tel Aviv University and Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (“Ichilov”) have measured subjects' memory without asking whether they remembered something or not - -simply by tracking their eye movements as they watched animation videos. The study demonstrated that people actually remember more than they report. Moreover, this method can be used to measure memory in subjects who cannot speak— including infants, patients with brain injuries, and even animals.

The groundbreaking study was led by Dr. Flavio Jean Schmidig, Daniel Yamin, Dr. Omer Sharon, and Prof. Yuval Nir from the Sagol School of Neuroscience, the Gray Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, and the Fleischman Faculty of Engineering at Tel Aviv University, as well as the Sagol Brain Institute at the Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (“Ichilov”). The paper was published in Communications Psychology.

"Memory is usually tested through direct questioning, with subjects verbally reporting whether they remember a certain event," explains Dr. Flavio Schmidig, currently completing his postdoctoral research in Prof. Yuval Nir’s lab at TAU. "For example, a subject might be shown a picture and asked if they remember having seen it before. However, this type of testing cannot be performed on animals, infants, patients with advanced Alzheimer’s, or people with head injuries who cannot speak. In this study we wanted to test memory in a more natural way, without asking people to remember."

"Gaze Memory" Illustration by Ana Yael

In the study, 145 healthy subjects watched specially created animation videos that included a surprising event - for example, a mouse suddenly jumping out of the corner of the frame. Tracking the subjects' eye movements across two separate viewings of the same films, the researchers found that during the second viewing, subjects shifted their gaze toward the area where the surprising event was about to occur. A comparison of eye movement data with verbal memory reports indicated that gaze direction was in fact a more accurate measure. In some cases, subjects said they did not remember the mouse, yet their gaze indicated that they did.

"The study proves that tracking eye movements can be an excellent alternative to verbal questions such as 'Do you remember this?'," says Daniel Yamin. "In a series of experiments, we demonstrated that gaze direction is a very sensitive gage of memory. Even when subjects said they didn’t remember, their gaze direction showed they did. This means that sometimes people remember, but can't say that they remember. By using AI machine learning techniques, it is possible to infer automatically, from just a few seconds of eye tracking, whether someone has seen a video before and formed a memory of it."

"When I ask you if you remember," adds Dr. Sharon, "you might give any of several answers: yes, no, not sure, etc. But when you look to the left of the frame due to a vague memory that something is about to happen there, finer nuances can be discerned. Now we have a tool for testing to what extent memory is present. Our new method is also more natural than traditional memory tests."

"The results of this study are especially relevant when verbal reports on memory cannot be obtained," adds Prof. Yuval Nir, the study's supervisor. "We believe that in the future this new method may be used for measuring memory functions in infants, Alzheimer's patients, and people with brain injury whose speech ability has been impaired. Gaze direction can be simply detected by the camera of a laptop or smartphone as the subject views a video - with no need for large, sophisticated equipment. The method has the potential for identifying memories even in situations that have so far been out of reach for us as scientists and clinicians."

Research

TAU researchers created a gene therapy that protects against hearing and balance impairments caused by inner ear dysfunction.

Scientists from the Gray Faculty of Medical & Health Sciences at Tel Aviv University introduced an innovative gene therapy method to treat impairments in hearing and balance caused by inner ear dysfunction. According to the researchers, “This treatment constitutes an improvement over existing strategies, demonstrating enhanced efficiency and holds promise for treating a wide range of mutations that cause hearing loss.”

The study was led by Prof. Karen Avraham, Dean of the Gray Faculty of Medical & Health Sciences, and Roni Hahn, a PhD student from the Department of Human Molecular Genetics and Biochemistry. The study was conducted in collaboration with Prof. Jeffrey Holt and Dr. Gwenaëlle Géléoc from Boston Children's Hospital and Harvard Medical School and was supported by the US-Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), the National Institutes of Health/NIDCD and the Israel Science Foundation Breakthrough Research Program. The study was featured on the cover of the journal EMBO Molecular Medicine.

Prof. Avraham explains: “The inner ear consists of two highly coordinated systems: the auditory system, which detects, processes, and transmits sound signals to the brain, and the vestibular system, which enables spatial orientation and balance. A wide range of genetic variants in DNA can affect the function of these systems, leading to sensorineural hearing loss and balance problems. Indeed, hearing loss is the most common sensory impairment worldwide, with over half of congenital cases caused by genetic factors. In this study, we aimed to investigate an effective gene therapy for these cases using an approach that has not been applied in this context before.”

Roni Hahn: “Gene therapy has emerged as a powerful therapeutic approach in recent years and is now being applied to a range of genetic disorders, including spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) and Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), as well as in cancer immunotherapy approaches such as CAR T-cell therapy. One of the treatment strategies includes the use of engineered viral vectors, in which the native DNA is replaced with a functional sequence of the target gene. These vectors utilize the virus's natural ability to enter cells to deliver the correct gene sequence, thereby restoring normal function. Many gene therapies utilize adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) to introduce therapeutic genetic material into target cells, and AAV-based gene therapy for hearing loss is currently in clinical trials, showing promising early results.

In this study, the researchers investigated a mutation in the CLIC5 gene, which is essential for maintaining the stability and function of hair cells in the auditory and vestibular systems. Deficiency of this gene causes progressive degeneration of hair cells, initially leading to hearing loss and later resulting in balance problems.

The researchers utilized an advanced, structurally optimized version of the AAV vector, the self-complementary AAV (scAAV). They found that this vector achieved faster and more efficient transduction of hair cells compared to traditional AAV methods, requiring a lower dose to achieve a similar therapeutic effect. In treated animal models, this approach prevented hair cell degeneration and preserved normal hearing and balance.

In summary, Prof. Avraham states: “In this study, we applied an innovative treatment approach for genetic hearing loss and found that it improves therapeutic effectiveness while also addressing combined impairments in hearing and balance. We anticipate that these findings will pave the way for developing gene therapies to treat a wide range of genetically caused hearing disorders."