New TAU Research Links Alzheimer's Disease to Brain Hyperactivity

Patients with Alzheimer's disease run a high risk of seizures. While the amyloid-beta protein involved in the development and progression of Alzheimer's seems the most likely cause for this neuronal hyperactivity, how and why this elevated activity takes place hasn't yet been explained — until now.

A new study by Tel Aviv University researchers, published in Cell Reports, pinpoints the precise molecular mechanism that may trigger an enhancement of neuronal activity in Alzheimer's patients, which subsequently damages memory and learning functions. The research team, led by Dr. Inna Slutsky of TAU's Sackler Faculty of Medicine and Sagol School of Neuroscience, discovered that the amyloid precursor protein (APP), in addition to its well-known role in producing amyloid-beta, also constitutes the receptor for amyloid-beta. According to the study, the binding of amyloid-beta to pairs of APP molecules triggers a signalling cascade, which causes elevated neuronal activity.

Elevated activity in the hippocampus — the area of the brain that controls learning and memory — has been observed in patients with mild cognitive impairment and early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Hyperactive hippocampal neurons, which precede amyloid plaque formation, have also been observed in mouse models with early onset Alzheimer's disease. "These are truly exciting results," said Dr. Slutsky. "Our work suggests that APP molecules, like many other known cell surface receptors, may modulate the transfer of information between neurons."

With the understanding of this mechanism, the potential for restoring memory and protecting the brain is greatly increased.

Building on earlier research

The research project was launched five years ago, following the researchers' discovery of the physiological role played by amyloid-beta, previously known as an exclusively toxic molecule. The team found that amyloid-beta is essential for the normal day-to-day transfer of information through the nerve cell networks. If the level of amyloid-beta is even slightly increased, it causes neuronal hyperactivity and greatly impairs the effective transfer of information between neurons.

In the search for the underlying cause of neuronal hyperactivity, TAU doctoral student Hilla Fogel and postdoctoral fellow Samuel Frere found that while unaffected "normal" neurons became hyperactive following a rise in amyloid-beta concentration, neurons lacking APP did not respond to amyloid-beta. "This finding was the starting point of a long journey toward decoding the mechanism of APP-mediated hyperactivity," said Dr. Slutsky.

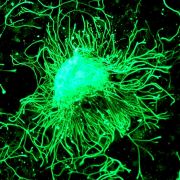

The researchers, collaborating with Prof. Joel Hirsch of TAU's Faculty of Life Sciences, Prof. Dominic Walsh of Harvard University, and Prof. Ehud Isacoff of University of California Berkeley, harnessed a combination of cutting-edge high-resolution optical imaging, biophysical methods and molecular biology to examine APP-dependent signalling in neural cultures, brain slices, and mouse models. Using highly sensitive biophysical techniques based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) between fluorescent proteins in close proximity, they discovered that APP exists as a dimer at presynaptic contacts, and that the binding of amyloid-beta triggers a change in the APP-APP interactions, leading to an increase in calcium flux and higher glutamate release — in other words, brain hyperactivity.

A new approach to protecting the brain

"We have now identified the molecular players in hyperactivity," said Dr. Slutsky. "TAU postdoctoral fellow Oshik Segev is now working to identify the exact spot where the amyloid-beta binds to APP and how it modifies the structure of the APP molecule. If we can change the APP structure and engineer molecules that interfere with the binding of amyloid-beta to APP, then we can break up the process leading to hippocampal hyperactivity. This may help to restore memory and protect the brain."

Previous studies by Prof. Lennart Mucke's laboratory strongly suggest that a reduction in the expression level of "tau" (microtubule-associated protein), another key player in Alzheimer's pathogenesis, rescues synaptic deficits and decreases abnormal brain activity in animal models. "It will be crucial to understand the missing link between APP and 'tau'-mediated signalling pathways leading to hyperactivity of hippocampal circuits. If we can find a way to disrupt the positive signalling loop between amyloid-beta and neuronal activity, it may rescue cognitive decline and the conversion to Alzheimer's disease," said Dr. Slutsky.

The study was supported by European Research Council, Israel Science Foundation, and Alzheimer's Association grants.

As originally reported by AFTAU.