An Underwater Journey Following the Vanishing of Sponge Species from the Shallow Water of the Israeli Coast

The researchers believe that the sharp rise in water temperatures may lead to the death and disappearance

Researchers from Tel Aviv University embarked on an underwater journey to solve a mystery: Why did sponges of the Agelas oroides species, which used to be common in the shallow waters along the Mediterranean coast of Israel, disappear? Today, this species can be found in Israel mainly in deep sponge grounds – rich habitats that exist at a depth of 100 meters. The researchers assess that the main reason for the disappearance of the sponges was the rise in seawater temperatures during the summer months, which in the past 60 years have risen by about three degrees.

The study was led by Prof. Micha Ilan and PhD student Tal Idan, in collaboration with Dr. Liron Goren and Dr. Sigal Shefer, all from the School of Zoology at the George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History. The article was published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Biology.

Tal Idan explains: “Sponges are marine animals of great importance to the ecosystem, and also to humans. They feed by filtering particles or obtain substances dissolved in the seawater and making them available to other animals, and are used as a habitat for many other organisms. Also, the sponges contain a wide variety of natural materials – chemicals that are used as a basis for the development of medicines. In our study, we focused on the Agelas oroides species – a common Mediterranean sponge that grew throughout the Mediterranean Sea, from a depth of less than a meter to 150 meters deep, but which has not been observed in Israel's shallow waters for over 50 years.”

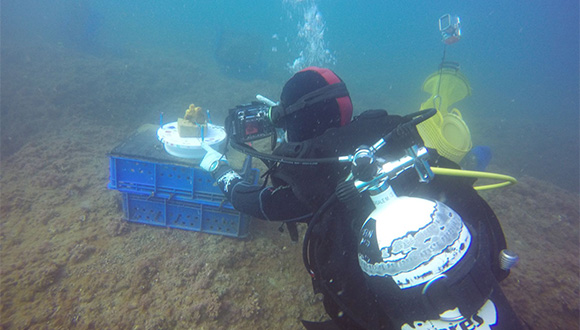

During the study, the researchers used a research vessel and an underwater robot belonging to the NGO “EcoOcean,” and with their help located particularly rich rocky habitats on the seabed at a depth of about 100 meters, approximately 16 kilometers west of Israeli shores. The most dominant animals in these habitats are sponges, which is why the habitats are called “sponge gardens.” The researchers collected 20 specimens of the Agelas oroides sponge, 14 of which were transferred to shallow waters at a depth of 10 meters, at a site where the sponge was commonly found in the 1960s. The remaining six specimens were returned to the sponge gardens from which they were taken, and used as a control group.

underwater robot. Photo: Tal Idan

The findings of the study showed that when the water temperature ranged from 18 to 26 degrees (in the months of March to May), the sponges grew and flourished: they pumped and filtered water, the action by which they feed, and their volume increased. However, as the water temperature continued to rise, the sponges’ condition deteriorated. At a temperature of 28 degrees, most of them stopped pumping water, and during the month of July, when the water temperature exceeded 29 degrees, within a short period of time all of the sponges that had been transferred to the shallow water died. At the same time, the sponges in the control group continued to enjoy a relatively stable and low temperature (between 17 and 20 degrees) which allowed them to continue to grow and thrive.

Thus, the researchers hypothesize that the decisive factor that led to the disappearance of the sponges from the shallow area was prolonged exposure to high seawater temperature. According to them, “In the past, the temperature would also reach 28.5 degrees in the summer, but only for a short period of about two weeks – so the sponges, even if damaged, managed to recover. Today, seawater temperatures rise above 29 degrees for three months, which likely causes multi-system damage in sponges, which leaves them no chance of recovering and surviving.”

Prof. Ilan: “From 1960 until today, the water temperature on the Israeli Mediterranean coast has risen by three degrees, which may greatly affect marine organisms, including sponges. Our great concern is that the changes taking place on our shores are a harbinger of what may take place in the future throughout the Mediterranean. Our findings suggest that continued climate change and the warming of seawater could fatally harm sponges and marine life in general.”

The researchers add that in recent years, in collaboration with the Ministry of Energy and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority, they have been conducting extensive surveys in a number of sponge gardens along the coast, with the clear aim of protecting these unique habitats and changing their status so that they are recognized as particularly vulnerable. Three of the research sites have now been made part of the Nature and Parks Authority's Marine Nature Reserves Program, in the hopes that they will eventually receive official recognition as marine nature reserves.