Preliminary TAU findings suggest noninvasive brain stimulation may reduce intrusive PTSD symptoms

Research

Preliminary TAU findings suggest noninvasive brain stimulation may reduce intrusive PTSD symptoms

A new study conducted at Tel Aviv University introduces an innovative approach to treating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generating particular interest in light of the sharp rise in the number of individuals coping with the condition following the events of October 7 and the Iron Swords War. According to the study’s preliminary findings, treatment using noninvasive brain stimulation succeeded in significantly reducing intrusive memories, such as flashbacks and intrusive thoughts, which are considered among the most severe and treatment-resistant symptoms of PTSD.

The study was conducted in the laboratories of Prof. Nitzan Censor and Yair Bar-Haim from the School of Psychological Sciences and the Sagol School of Neuroscience at Tel Aviv University. It was led by doctoral students Or Dezachyo and Noga Yair, in collaboration with the laboratory of Prof. Ido Tavor. The research team included Noga Mendelovitch, Dr. Niv Tik, Dr. Haggai Sharon of Tel Aviv Sourasky Medical Center (Ichilov), and Prof. Daniel Pine of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in the United States. The study was published in the scientific journal Brain Stimulation.

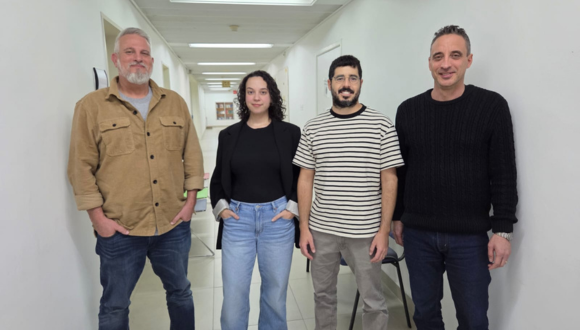

Research team (Left to right): Prof. Yair Bar-Haim, Noga Yair, Or Dezachyo and Prof. Nitzan Censor

PTSD affects millions of people worldwide, including soldiers and survivors of terrorist attacks, traffic accidents, and violence. Despite advances in psychological and pharmacological treatments, only about 50% of patients respond well to existing therapies, and intrusive memories continue to burden many of them years after the traumatic event. These memories are not just distressing thoughts; they are vivid, tangible experiences that reactivate the body and emotions as though the trauma were happening all over again.

The researchers focused on the hippocampus — a deep brain structure responsible for the processing, storage, and retrieval of memories. Because direct stimulation of deep brain regions requires invasive intervention, the team employed an indirect and sophisticated method: they identified superficial brain regions that are functionally connected to the hippocampus and stimulated them using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). The precise stimulation site was determined individually for each participant based on fMRI scans, allowing for a personalized treatment approach.

Ten adults with PTSD participated in the initial study, undergoing five weekly treatment sessions. During each session, the traumatic memory was first deliberately reactivated, after which brain stimulation was applied — precisely at the stage when the memory is in a “flexible” state and more open to change, within a process known as reconsolidation. The researchers’ aim was to influence the way the memory is re-stored in the brain, thereby alleviating post-traumatic symptoms.

The results showed a sharp reduction in the severity of post-traumatic symptoms, particularly in the frequency and intensity of intrusive memories, with participants demonstrating consistent improvement. At the same time, brain imaging revealed reduced connectivity between the hippocampus and the stimulation regions — evidence that the effects were not merely subjective but reflected a real change in brain activity.

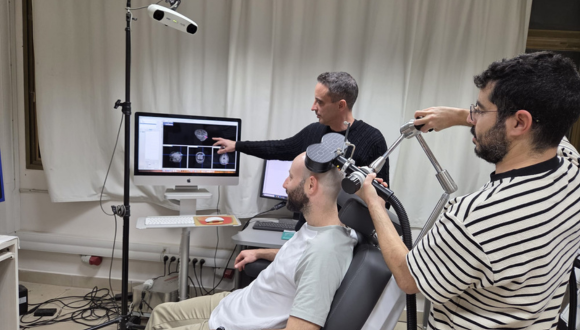

Illustration of the experimental setup

These findings carry particular importance for IDF soldiers, members of the security forces, civilians exposed to the terror attacks of October 7, survivors of the massacre, and victims of shootings and abductions — Israeli populations in which the prevalence of PTSD is expected to be especially high. Many of them report experiencing intense intrusive memories months after the events. The potential development of a short, noninvasive treatment that directly targets the mechanisms underlying traumatic memories could become a valuable component of the national rehabilitation effort.

According to the researchers, although this was a preliminary study conducted in a small group and did not include a control group, it provides clear proof of feasibility. Larger, controlled clinical trial is already underway at Tel Aviv University, and is required to assess the method’s effectiveness and long-term impact. If the findings are confirmed, this may represent a fundamental shift in the way traumatic memories are treated — addressing not only its emotional consequences, but the underlying neural root itself.

Prof. Nitzan Censor concludes: “These preliminary findings point to a conceptual shift in how we can approach the treatment of PTSD. We are attempting to intervene, in a targeted manner, in the brain mechanism of memory itself — at the moment when it ‘reopens’ and becomes amenable to change. The fact that we observed a consistent reduction in intrusive memories, alongside a measurable change in brain activity, is encouraging. It is important to emphasize that these are still very early results. Nevertheless, especially in light of the current reality in Israel, we hope that continued, comprehensive clinical research will eventually make it possible to develop a noninvasive and accessible treatment that will help many soldiers and civilians return to functional lives, free from the constant intrusion of traumatic memories.”

Research

Researchers warn that patterns seen in the Canary Islands may emerge in other regions worldwide.

A global study by an international research team, including Prof. Omri Bronstein of the School of Zoology, Wise Faculty of Life Sciences and the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History at Tel Aviv University - who is leading global efforts to study the wave of sea urchins mass mortalities around the world, presents new and particularly alarming findings: for the first time, evidence of apparent local sea urchin extinction has been found in the Canary Islands.

The study revealed that the genus Diadema (the long-spined black sea urchins many of us are familiar with) is no longer able to produce offspring at this site — a finding that likely indicates local extinction.

The study was carried out by an international consortium including Tel Aviv University scientists in collaboration with researchers from Spain and the Canary Islands. The findings were published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.

Prof. Bronstein describes the sequence of events over recent decades: “In 1983–84, a mass mortality event of Diadema sea urchins was recorded in the Caribbean islands in the western Atlantic Ocean. This die-off triggered a dramatic ecological shift in the region: with the sea urchins — the habitat’s primary algae grazers — gone, vast algal fields spread, blocking sunlight and causing severe, irreversible damage to coral reefs in the region. In 2022, another mortality event struck the Caribbean, and for the first time the pathogen responsible for the lethal disease was identified. This epidemic spread to the Red Sea by 2023, and by 2024 it was also detected in the Western Indian Ocean, off the coast of Reunion.”

In the current study, a formerly undetected mass mortality event was identified in the Canary Islands, off the coast of Morocco in the eastern Atlantic Ocean, which in fact occurred as early as mid-2022. According to the researchers, this event represents the “missing link” in the disease’s geographic spread. The study also revealed a particularly troubling finding, which likely points to the potential local extinction of the species in the Canary Islands. The study was based on extensive observational data collected through local citizen science, alongside scientific surveys, satellite data analysis (remote sensing), and the collection of samples from the seafloor by the research team.

Prof. Bronstein explains: “Sea urchins reproduce by releasing sperm and eggs into the seawater, where fertilization produces millions of embryos that drift as plankton in the water column. After several days to weeks (depending on the species), the larvae settle on the seabed and develop into juvenile urchins — a process known as ‘recruitment.’ In this study, we discovered that for the first time in history, there are no new juvenile urchins being recruited across several Canary Islands, indicating that the recruitment process has halted since the extensive mortality event that took place there. In other words, the die-off of the adult urchins has been so widespread that the species is no longer able to produce a next generation, if no recruitment occurs, the species may disappear from the region’s ecosystem.”

The researchers note that sea urchin populations are typically characterized by fluctuations — they often decline and later recover. This time, however, the situation is far more severe and appears to be an extinction event rather than a transitional phase. The researchers warn that the pattern observed in the Canary Islands may also unfold in other regions around the world where unprecedented sea urchin mass mortality events have been recorded in recent years — including the Red Sea coast and the coral reef of the Gulf of Eilat.

Prof. Bronstein concludes: “In this study, we identified a mass mortality event of sea urchins that occurred in mid-2022 in the Canary Islands. In its aftermath, it became clear that the affected species is no longer capable of successfully reproducing in this area — a finding that may lead to local extinction, which is expected to have severe ecological consequences. A likely outcome would be the uncontrolled proliferation of algae, which would affect the entire ecosystem — although at this stage, it is difficult to predict exactly in what way.

Prof. Omri Bronstein

Prof. Omri Bronstein is a marine biologist whose research focuses on molecular ecology and the processes that lead to the formation of new species. He is a senior faculty member at the School of Zoology in the George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences and at the Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, Tel Aviv University.

Research

New research reveals that activating the brain’s reward system through positive anticipation strengthens the immune response and increases antibody production

Can positive anticipation that activates the brain’s reward system strengthen the body’s immune defenses? A new study by Tel Aviv University, the Technion, and Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov), published in the prestigious journal Nature Medicine, provides the first evidence in humans that brain activity associated with the expectation of reward has a measurable effect on the body’s response to a specific vaccine.

Training the Brain’s Reward SystemThe study was conducted through a collaboration between two research groups: the laboratory of Prof. Talma Hendler, from the School of Psychological Sciences and the Gray Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, together with her former PhD student Dr. Nitzan Lubianiker, at Tel Aviv University and the Sagol Brain Institute at Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov); and the laboratory of Prof. Asya Rolls from The George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, together with her former student Dr. Tamar Koren of the Technion and the Department of Pathology at Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov).

Eighty-five healthy volunteers participated in the experiment. Some underwent special brain training using fMRI neurofeedback technology — a method that enables individuals to learn, in real time, to regulate activity in specific brain regions through reinforcing learning. The aim of the brain training was to increase activity in a key region of the brain’s reward system including the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA), which is responsible for dopamine release in the context of mental activity related to the expectation of positive outcomes and motivation to obtain rewards. Participants were instructed to modulate their brain activity using various mental strategies (e.g. thoughts feelings memories) while monitoring positive feedback about the strategy that was saucerful in regulating their brain.

Immediately after completing the brain training, all participants received a hepatitis B vaccine. The researchers then tracked the immune response through a series of blood tests, measuring levels of specific antibodies produced following the vaccination.

The results showed that participants who succeeded in significantly increasing activity in the brain’s reward region also demonstrated a greater increase in antibody levels after vaccination. The association was specific to the VTA and was not observed in other brain regions used for control purposes (such as the hippocampus), nor in other reward-system areas linked to different reward-related experiences such as pleasure and satisfaction. In other words, the effect was both anatomically and mentally specific.

Dr. Nitzan Lubianiker, photo credit: Sameer Khan/Fotobuddy

Furthermore, an in-depth analysis of the mental strategies participants used during training of the VTA (and not other regions) revealed that those who focused on positive anticipation — feelings of excitement, belief in a good outcome, or the expectation of something positive about to happen (such as a favorite food or a long-awaited meeting) — were able to maintain higher VTA brain activity over time, which was also associated with a better immune response. In other words, the researchers identified a link between reward-system brain activity, a mental state of positive anticipation, and the body’s response to an immune challenge.

According to the research team, this is not “positive thinking” in the popular sense or a New Age slogan, but a measurable neurobiological mechanism — related, among other things, to the well-known placebo effect in medicine (a therapeutic response beyond a specific medical intervention). “We show that mental states have a clear brain signature, and that this signature can influence physiological systems such as the immune system,” explain the researchers.

While the study does not propose a substitute for vaccines or medical treatment, it opens the door to new, noninvasive approaches that may one day strengthen immune responses, improve the effectiveness of medical treatments, and even contribute to fields such as immunotherapy and the treatment of chronic immune pathologies. The researchers note that the study’s findings underscore a broader message: the mind–body connection is not merely a theoretical concept, but a real biological process that can be measured, trained, and potentially harnessed to promote better health.

Prof. Talma Hendler, Photo credit: Tel Aviv Medical Center (Ichilov).

The research team adds that the findings highlight the potential inherent in integrating neuroscience, psychology, and medicine. “Our study shows that the brain is not only a system that responds to the body’s state of health, but also an active player that influences it,” say Prof. Talma Hendler, Prof. Asya Rolls, Dr. Nitzan Lubianiker, and Dr. Tamar Koren. “The ability to consciously activate brain mechanisms associated with positive anticipation opens a new avenue for research and future treatments — as a complement to existing medicine, not as a replacement. In the future, it may be possible to develop simple, noninvasive tools to help strengthen immune responses and enhance the effectiveness of medical treatments by relying on the brain’s natural capacity to influence the body. However, it is important to emphasize that activation of the reward system and its effect on immune response vary between individuals. Therefore, this approach cannot replace existing medical treatments, but may well serve as an additional supportive component.”

Research

A TAU–University of Haifa study solves a long-standing mystery about rhythmic movement in nature

A joint study by Tel Aviv University and the University of Haifa set out to solve a scientific mystery: how a soft coral is able to perform the rhythmic, pulsating movements of its tentacles without a central nervous system. The study’s findings are striking, and may even change the way we understand movement in the animal kingdom in general, and in the corals studied in particular.

The study was led by Elinor Nadir, a PhD student at Tel Aviv University, under the joint supervision of Prof. Yehuda Benayahu of the School of Zoology at Tel Aviv University and Prof. Tamar Lotan of the Department of Marine Biology at the Leon H. Charney School of Marine Sciences at the University of Haifa. The findings were published in the prestigious scientific journal PNAS.

The research team discovered that the soft coral Xenia umbellata — one of the most spectacular corals on Red Sea reefs — drives the rhythmic movements of its eight polyp tentacles through a decentralized neural pacemaker system. Rather than relying on a central control center, a network of neurons distributed along the coral’s tentacle enables each one to perform the movement independently, while still achieving precise, collective synchronization.

“It’s a bit like an orchestra without a conductor,” explains Prof. Tamar Lotan of the School of Marine Sciences at the University of Haifa. “Each tentacle acts independently, but they are somehow able to ‘listen’ to each other and move in that perfect harmony that so captivates observers. This is a completely different model from how we understand rhythmic movement in other animals.”

Corals of the Xeniidae family are known for their hypnotic movements — the cyclic opening and closing of their tentacles. Until now, however, it was unclear how they perform this. To investigate, the researchers conducted cutting experiments on the coral’s tentacles and examined how they regenerated and restored their rhythmic motion. To their surprise, even when the tentacles were cut off and separated from the coral — and even when further divided into smaller fragments — each piece retained its ability to pulse independently.

Subsequently, the researchers conducted advanced genetic analyses and examined gene expression at different stages of tentacle regeneration after separation from the coral. They found that the coral uses the same genes and proteins involved in neural signal transmission in far more complex animals, including acetylcholine receptors and ion channels that regulate rhythmic activity. According to the researchers, this discovery suggests that the origin of rhythmic movements — familiar to us from those underlying breathing, heartbeat, or walking — is far more ancient than previously thought. The corals studied demonstrate how coordinated movement can emerge from a simple, distributed system, long before sophisticated control centers evolved in the brains of advanced animals.

Prof. Benayahu adds: “It is fascinating to reach the conclusion that the same molecular components that activate the pacemaker of the human heart are also at work in a coral that appeared in the oceans hundreds of millions of years ago. The coral we studied allows us to look back in time, to the dawn of the evolution of the nervous system in the animal kingdom. It shows that rhythmic and harmonious movement can be generated even without a brain — through remarkable communication among nerve cells acting together as a smart network. There is no doubt that this study adds an important layer to our understanding of the wonders of the coral reef animal world in general, and of corals in particular, and underscores the paramount need to preserve these extraordinary natural ecosystems.”

Research

New TAU study shows facial mimicry is part of how we make choices

Imagine sitting across from someone describing two movies to you. You listen attentively, trying to decide which one interests you more — but during that time, without noticing, your face already reveals what you prefer. You smile slightly when they smile, raise your eyebrows when they surprise you, tense your muscles when they emphasize something. This phenomenon is called facial mimicry — and it turns out to be a better predictor of your choice than anything else.

This is the central finding of a new study from the School of Psychological Sciences at Tel Aviv University, led by doctoral student Liron Amihai in the lab of Prof. Yaara Yeshurun (together with Elinor Sharvit and Hila Man), in collaboration with Prof. Yael Hanein of TAU’s Fleischman Faculty of Engineering. The study was published in Communications Psychology.

The study was conducted with dozens of pairs in which one person described two different films to their partner, after which the participants had to choose which film they preferred to watch. Using unique technology, the research team was able to track micro-movements of the face that are not visible to the naked eye.

Research team - Left to right - Prof. Yaara Yeshurun & Liron Amihai

The findings showed that participants consistently preferred the option during which they showed more mimicry of the speaker's positive expressions . They did so even when they were explicitly instructed to choose according to their personal taste and not according to the speaker.

This finding is particularly interesting given that the listeners’ own facial expressions (for example, how much they smiled in general) did not predict their choice, but rather the degree to which they mimicked the speaker.

In another phase of the experiment, participants listened to an actress reading the movie summaries using audio only, without any video. Even though they could not see her face, the researchers found that the participants mimicked her “smile in the voice” and this mimicry again predicted their choice.

The research team: “The study indicates that facial mimicry is not only a social mechanism that helps us connect with other people. It likely also serves as an ‘internal signal’ to the brain that is indexing agreement.”

.png)

Illustration of a participant in the study with an EMG electrode measuring her facial expressions activation

Liron Amihai explains: “The study showed that we are not just listening to a story — we are actually being ‘swept’ toward the speaker with our facial expressions’ mimicry, and this muscular feedback might influence our decisions. This mimicry often happens automatically, and it can predict which option we will prefer long before we think about it in words. Facial mimicry, therefore, is not merely a polite gesture, but also a part of the decision-making system.”

Liron concludes: “With the help of this technology and these findings, we may be able in the future to build systems that identify emotional preferences naturally — without asking a single question.

In conclusion, the study illustrates that decision-making is not only a matter of thought — but also of feeling, bodily response, and unconscious communication. Facial mimicry emerged as a significant predictor of our preferences. This is a meaningful step toward understanding how we choose, feel, and empathize with others, and it has many implications for the worlds of advertising, marketing, and decision-making processes.”

Research

For the first time, researchers uncover the biological mechanism that enables breast cancer to spread to the brain, opening new paths for treatment and early detection

A large-scale international study, led by researchers from the Gray Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences at Tel Aviv University, has uncovered a mechanism that allows breast cancer to send metastases to the brain — a highly lethal occurrence for which there is currently no effective treatment. The findings could enable the development of new drugs and personalized monitoring for early detection and treatment of brain metastases.

The groundbreaking study was led by Prof. Uri Ben-David and Prof. Ronit Satchi-Fainaro, along with researchers Dr. Kathrin Laue and Dr. Sabina Pozzi from their laboratories at the Gray Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences at Tel Aviv University, in collaboration with dozens of researchers from 14 laboratories in 6 countries (Israel, the United States, Italy, Germany, Poland, and Australia). The article was published in the journal Nature Genetics.

Prof. Satchi-Fainaro explains: “Most cancer-related deaths are not caused by the primary tumor but by its metastases to vital organs. Among these, brain metastases are some of the deadliest and most difficult to treat. One of the key unresolved questions in cancer research is why certain tumors metastasize to specific organs and not others. Despite the importance of this phenomenon, very little is known about the factors and mechanisms that enable it. In this study, we joined forces to deepen our understanding and seek answers."

Left to right: Prof. Satchi-Fainaro & Prof. Uri Ben-David.

The current study combined two distinct approaches to cancer research: Prof. Satchi-Fainaro’s lab, which studies the interactions between cancer cells and their surrounding environment (the tumor microenvironment), and Prof. Ben-David’s lab, which investigates chromosomal changes that characterize cancer cells. The complex study involved numerous scientific methods and technologies, including clinical and genomic data analysis of tumors from breast cancer patients, genetic, biochemical, metabolic, and pharmacological experiments in cultured cancer cells, and functional experiments in mice.

The researchers first identified a specific chromosomal alteration in breast cancer cells that predicts a high likelihood of brain metastases. Prof. Ben-David explains: “We found that when chromosome 17 in a cancer cell loses a copy of its short arm, the chances of the cell sending metastases to the brain greatly increase. We also discovered that the reason for this is the loss of an important gene located on this arm. This gene is p53, often referred to as ‘the guardian of the genome,’ and it plays a crucial role in regulating cell growth and division. We discovered that the absence of a functional p53 is essential for the formation and proliferation of cancerous brain metastases. When we injected mice brains with cancer cells with or without functional p53, we found that cells with disrupted p53 activity thrived much more. We sought to understand the mechanism causing this.”

Prof. Satchi-Fainaro adds: “The brain’s environment is fundamentally different from that of the breast, where the primary tumor develops, and the question is how a breast cancer cell, adapted to its original environment, can adjust to this foreign one. According to our findings, this adaptation is closely linked to the impairment of the p53 gene. We found that p53 regulates the synthesis of fatty acids, a metabolic process particularly vital in the brain environment. This means that cells with damaged p53, or without p53 at all, produce more fatty acids compared to normal cells, which in turn enables them to grow and divide more rapidly in the brain.”

Left to right: Dr. Kathrin Laue & Dr. Sabina Pozzi.

The next phase of the study focused on the components of the brain environment and the communication between brain cells and cancer cells. The researchers identified heightened interaction between cancer cells with damaged p53 and astrocytes — support cells in the brain that secrete substances aiding neurons. In the absence of p53, the cancer cells hijack the substances secreted by the astrocytes and use them to produce fatty acids. The researchers identified a specific enzyme named SCD1 — a key enzyme in fatty acid synthesis — whose expression and activity levels are significantly higher in cancer cells with impaired or missing p53.

Prof. Ben-David: “Once we identified the mechanism and its key players, we sought to use the findings to search for a potential drug for brain metastases. We chose to focus on the SCD1 enzyme and tested the effectiveness of several drugs that inhibit its activity and are currently under development. These drugs were originally indicated for other diseases, but we found that SCD1 inhibition in brain metastatic cells with impaired p53 was effective and significantly hindered the development and proliferation of cancerous metastases — both in mice and in samples from brain metastases of women with breast cancer.”

The researchers add that their findings may also assist doctors and patients in predicting disease progression: even at an early stage of breast cancer, it is possible to identify whether there is a p53 mutation (or deletion of the short arm of chromosome 17), which significantly increases the risk of brain metastases later on. For example, doctors could avoid prescribing aggressive biological treatments with severe side effects for patients not at high risk of brain metastases, while opting for aggressive treatment when the risk is elevated. In addition, physicians can tailor monitoring to the patient’s risk level — such as frequent brain MRI scans for patients at increased risk of brain metastases. This type of intensive monitoring would allow for early detection and treatment, significantly increasing the chances of recovery.

The researchers conclude: “In this study, we joined forces in an extensive international effort to address a highly important question: What is the mechanism that enables breast cancer to metastasize to the brain? We identified several characteristics of cancer cells causally linked to this deadly phenomenon, and the findings allowed us to propose new drug targets for brain metastases — a condition for which no effective treatment currently exists. Moreover, we tested drugs that inhibit a specific metabolic mechanism, SCD1 inhibitors, and found them to be effective against brain metastases. Additionally, our findings are expected to enhance oncologists' ability to identify patients at elevated risk and prepare accordingly. While the road ahead is still long, the potential is immense.”

The project was supported by competitive research grants from the Israel Science Foundation (ISF), the Israel Cancer Research Fund (ICRF), and the Spanish bank Fundacion “La Caixa.” It is also part of broader research being conducted in Prof. Satchi-Fainaro’s lab, supported by an Advanced Grant from the European Research Council (ERC), ERC Proof of Concept (PoC), and the Kahn Foundation, as well as broader research being conducted in Prof. Ben-David’s lab, supported by an ERC Starting Grant.